“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world”

The following quotation is often, most likely incorrectly, attributed to Albert Einstein:

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t …pays it.”

“Compound interest” refers to the practice of continually reinvesting earnings received on investments over long periods of time (e.g. 40 years), as a mechanism to accumulate wealth. Regardless of who was responsible for the hyperbolic statement above, it’s a reality that the considerable power of compounding is not well understood by most and, even if understood, requires an ability to defer gratification that seems to be beyond many.

Like the achievement of a lot of generally desired things in life (e.g. becoming physically fit, losing weight, competence at a selected sport, hobby or musical instrument), accumulating wealth through compounding takes long term commitment and discipline. Early in the process, there may be little apparent reward for considerable sacrifice, making it difficult to resist the temptation to spend now rather than save and/or to think that there are few consequences for deferral of saving to later in life.

The purpose of this article is to simply and graphically demonstrate the power of compounding. It shows that the earlier and longer you commit to a disciplined saving regime the more successful you will be at accumulating wealth to meet your lifestyle goals. It also reveals that deferral of saving, for whatever reason, early in your working life significantly increases the difficulty of meeting a wealth accumulation objective later in life e.g. for retirement.

The rewards of compounding accrue to the patient and disciplined

The following are the key simple assumptions for the initial analysis:

- A 25-year-old, starting with nil investment wealth, saves $10,000 p.a. (after-inflation) to age 65; and

- The after-inflation, after tax return on investment is 5% p.a.

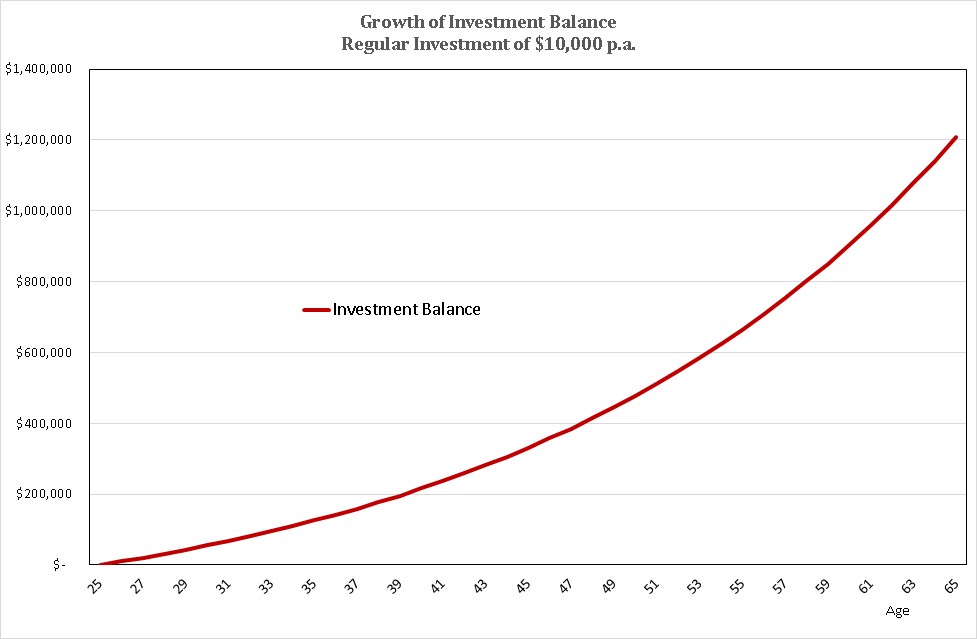

Based on the above assumptions, the chart below shows the implied growth of the real (i.e. after-inflation) investment balance over the 40 year saving period.

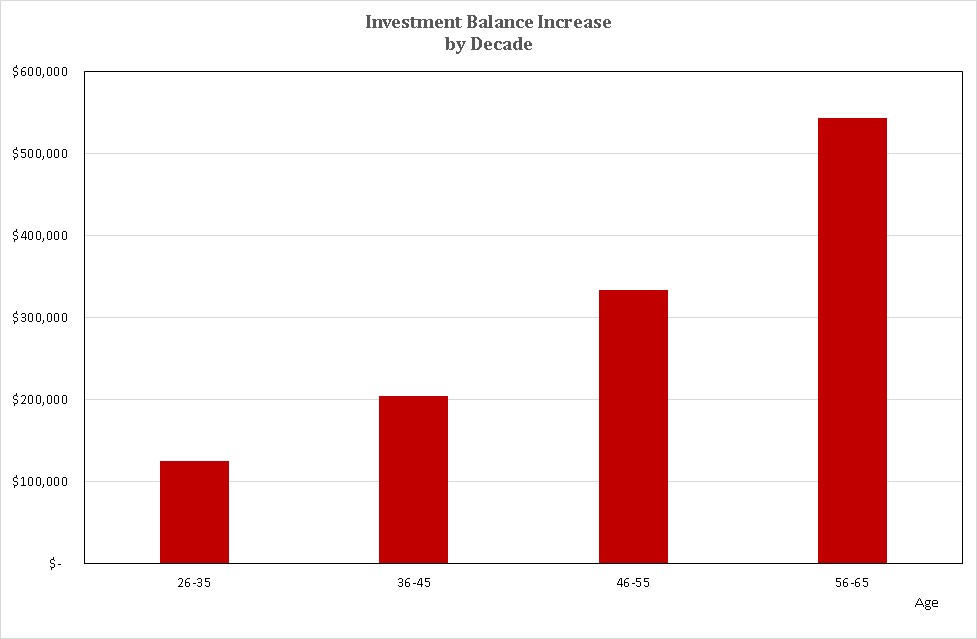

From zero to a little over $1.2 million, investing $10,000 p.a. for forty years (i.e. a total of $400,000), looks a pretty good return for some disciplined saving. But it is interesting to look more closely at how the investment balance growth occurs, over time. The chart below shows the growth of the investment balance for each decade of the 40-year investment period:

Relatively little growth, in excess of savings, occurs in the first decade. It would be easy to think during this period that it’s just not worth the effort. But by the fourth decade, the reward for perseverance is huge with the investment balance increasing about $550,000, despite new investment of only $100,000 (i.e. $10,000 p.a.) over that ten years.

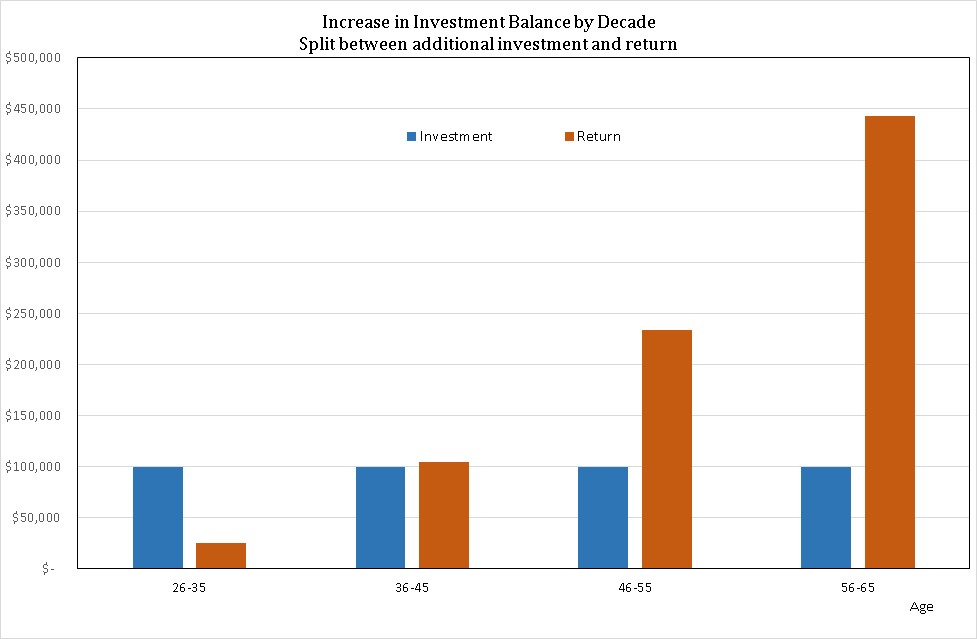

The following chart reveals more clearly what is going on, breaking the total growth in investment balance for each decade into its component parts i.e. additional investment and investment return.

There is relatively little investment return in the first decade, but beyond that the result of earning investment return on investment return (i.e. compounding) exceeds the amount of additional investment. By the fourth decade, investment return is more than four times the additional investments made!

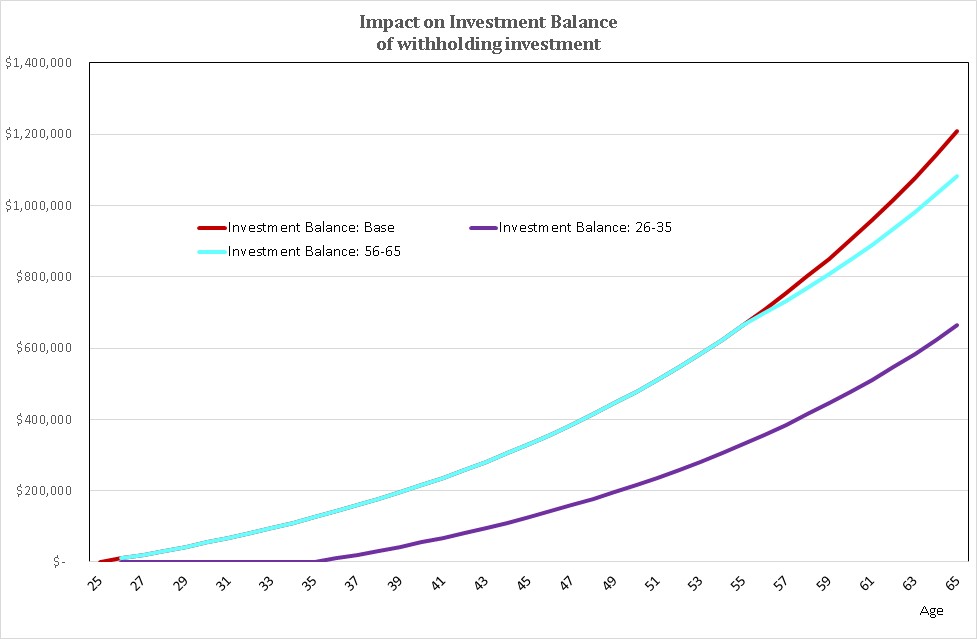

So what if our 25-year-old isn’t able to maintain their savings discipline over the entire 40-year period. The chart below compares the scenario described above (i.e. Investment Balance: Base) with two alternatives:

- Investment Balance: 26-35: No savings are made in the first decade, followed by $10,000 p.a. for the next three decades; and

- Investment Balance: 56-65: $10,000 p.a. saving for the first three decades, then no additional investments in the final decade.

The consequences of deferring saving are clear. By failing to save $10,000 p.a. in the first decade (i.e. $100,000 in total), the investment balance at age 65 is about $544,000 less than it would otherwise have been – a 45% reduction! To compensate for the lack of savings in the first decade, savings would need to increase to almost $18,200 p.a. (i.e. 82% more) for the final three decades to achieve the Base case investment balance.

The penalty for failing to save in the final decade is much less severe, because the accumulated investment balance after three decades continues to earn a significant total return. The $126,000 shortfall compared with the base case reflects primarily the $100,000 less in additional saving and $26,000 loss of earnings on those savings.

The consequences of deferring savings are unavoidable

Although the above analysis is simple, it has some powerful lessons including:

- To benefit from the power of compounding, the ability to defer gratification is critical – long term commitment and discipline are essential;

- The longer you defer implementing a disciplined savings programme, the more difficult it becomes to save enough to reach a desired wealth accumulation target. Defer too long and it becomes virtually impossible; and

- If your savings programme is to waver, it’s better (in terms of wealth accumulation) that it happens later rather than earlier.

For those with discipline and a long term focus, the rewards of letting compounding work can be substantial, including significant financial flexibility in later life.

But for those who choose to defer saving and spend now, an almost inevitable consequence is such financial flexibility becomes exponentially more difficult to achieve the longer they defer. Unfortunately, that painful reality may only be appreciated when it’s too late in life to do anything about it!