The “experts” claim housing is as affordable as it was in the 1980’s …

We have discussed housing affordability, either directly or indirectly, in a number of previous articles e.g. “Are Australian house prices too high?” of August 2012. Our view of almost three years ago was that housing prices then were incompatible with the average 35 year old being able to purchase a home and save sufficient to finance a desired retirement by age 65.

We never predict the direction of housing or any other asset prices – at least in this area, we know what we don’t know. But we shake our heads in amazement as house prices continue to rise, particularly in Sydney, while income growth flattens further exacerbating the already unsatisfactory situation identified in August 2012.

And one factor almost certainly driving house price growth is the oft-repeated claim by “experts” that interest rate reductions mean that home loans are as, or more, affordable than they were in the 1980’s (see, for example, “New research shows Sydney property more affordable than 26 years ago”, an article in “The Sydney Morning Herald” discussing research by BIS Shrapnel and “Housing affordability”, an extract from “Myth Busting Economics”, a book by private sector economist, Stephen Koukoulas).

The argument essentially is that although median house prices are now about five times annual income compared with approximately three times income in the 1980’s, requiring a proportionate increase in housing loan size, this has been offset by the fall in interest rates. As a result, actual loan repayments, as a percentage of income, have not changed greatly. Koukoulas concludes:

“…it has never been easy to get into the housing market for the first time or to upgrade to a nicer house, but it is no harder now than it was in the past.”

Many are seduced by this logic, particularly since it often reinforces an existing affinity to residential property as an investment. But our view is that the logic is badly flawed.

…But the “experts” are suffering from money illusion

We think the “experts” are suffering from what economists call “money illusion”. Their focus is on current loan repayments, rather than future “real” loan payments that take account of actual and expected inflation. For example, a current loan repayment of $30,000 p.a. will cost only $5,353 in 20 years’ time if inflation is 9% p.a., but $20,189 if inflation is 2% p.a.

The implications of inflation for affordability are significant and, if better understood, would almost certainly change decision making. The rest of this article attempts to make this more concrete.

It is first important to understand that interest rates comprise two components – a real rate and an expectation of inflation. In the 1980’s, interest rates were relatively high because inflation expectations were high. Currently, interest rates are relatively low because inflation expectations are much lower than they were in the 1980’s.

Let’s look at two housing loan scenarios to illustrate the implications of this. The first, which we call the “1980’s Scenario”, assumes a real interest rate of 3% p.a. and inflation expectations of 9% p.a. This implies an actual interest rate of about 12% p.a. and is indicative of 1980’s housing loan rates. The second, the “2010’s Scenario”, also assumes a real interest rate of 3% p.a. but inflation expectations of only 2% p.a., implying an actual interest rate of about 5% p.a. i.e. indicative of current housing loan interest rates.

Next, we assume housing prices are three times income for the 1980’s Scenario and five times income for the 2010’s Scenario. Based on an income of $100,000, the house price is $300,000 for the 1980’s Scenario and $500,000 for the 2010’s Scenario. In both scenarios, banks are willing to lend 80% of the house price (i.e. a 20% deposit is required) at the relevant interest rate, repayable in equal annual instalments over 25 years.

For the 1980’s Scenario, this implies a $240,000 loan and $60,000 deposit, with annual loan payments of $31,175. For the 2010’s Scenario, it means a loan of $400,000, deposit of $100,000 and annual loan payments of $28,552. As the “experts” claim, loan repayments are no more in the 2010’s Scenario than in the 1980’s Scenario – in fact, for our example, they are less.

But what if inflation expectations at the time of taking out the loan prove to be correct – what are the real (i.e. inflation adjusted) loan repayments for each scenario. The charts below show the implied real and actual repayments for each case:

With inflation at 9% p.a. (1980’s Scenario), real repayments fall quickly from 28.6% of initial income at Year 1 to only 3.6% of initial income at Year 25. But with inflation at 2% p.a.(2010’s Scenario), real repayments only decline from 28.0% of initial income at Year 1 to 17.4% of initial income at Year 25 – even after 25 years, mortgage payments are still consuming a large chunk of initial income.

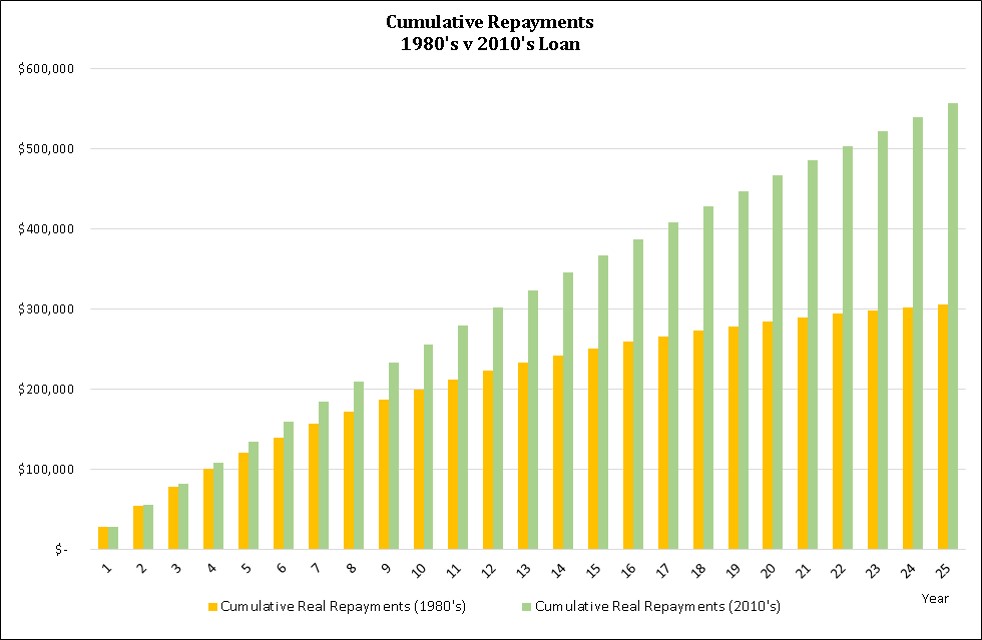

The chart below compares cumulative real loan repayments for each scenario:

Total real repayments are expected to be $557,400 for the 2010’s scenario compared with $306,200 for the 1980’s Scenario i.e. a massive 82% higher. Together with the need for an additional $40,000 deposit, the 2010’s borrower should expect to commit much more of their real incomes to house purchase than the 1980’s borrower, leaving commensurately less to direct to other spending and saving for retirement.

Unfortunately, it’s going to take a while for the penny to drop for borrowers in the current housing market. If current inflation expectations prove roughly right, mortgage commitments will remain a real burden for much longer than they were probably expecting and much longer than experienced by baby boomers in the 1980’s.

Housing has never been less affordable

Current loan repayments don’t measure the cost of servicing a mortgage or housing affordability. The cost of servicing a mortgage is the sum of actual inflation adjusted loan repayments over the life of the loan.

And based on current house prices relative to income and inflation expectations built into current home loan interest rates, house purchase will consume much more of households’ future income than it ever has in the past i.e. in this sense, housing has never been less affordable.

Unless saved by dramatic falls in real interest rates and/or a sharp acceleration in actual inflation, the term “mortgage slave” has never been more appropriate to describe those who are borrowing heavily to purchase a home in today’s market.