Concentrate your investments to make and lose a lot of money

The following recent Twitter exchange was the catalyst for this article:

“If you want to make a lot of money, resist diversification.” – Jim Rogers

— Jack Damn (@JackDamn) March 2, 2016

True. But the data says you are much more likely to lose a lot of money. https://t.co/BP9q2V32Pg

— Bob Seawright (@RPSeawright) March 2, 2016

The initial tweet above is a quote from Jim Rogers, a well known US investment commentator, who believes he can reliably pick investment winners and time investment markets, despite robust academic research suggesting such skills are both incredibly rare and difficult to identify. However, his view that if you want to make a lot of money you should avoid diversification (i.e. spreading your investments as broadly as you cost effectively can) is undoubtedly correct.

However, the response from Bob Seawright, who is much more aligned with our research based investment philosophy, suggests Rogers’ “wisdom” is only half the story. Many investors, usually to their detriment, are either ignorant of the risk reduction benefits of diversification or foolishly believe they have the skills to beat the odds by concentrating their investment holdings. Our article, “Concentrated investments are bad bets”, explains why, on average, a highly concentrated investment strategy is a losing proposition.

The Twitter exchange prompted me to have a closer look at the share price history of a share market listed engineering services company called WorleyParsons. It regularly attracts my attention, as its daily share price movements, both up and down, are often in the top three market movers for the largest 100 listed companies.

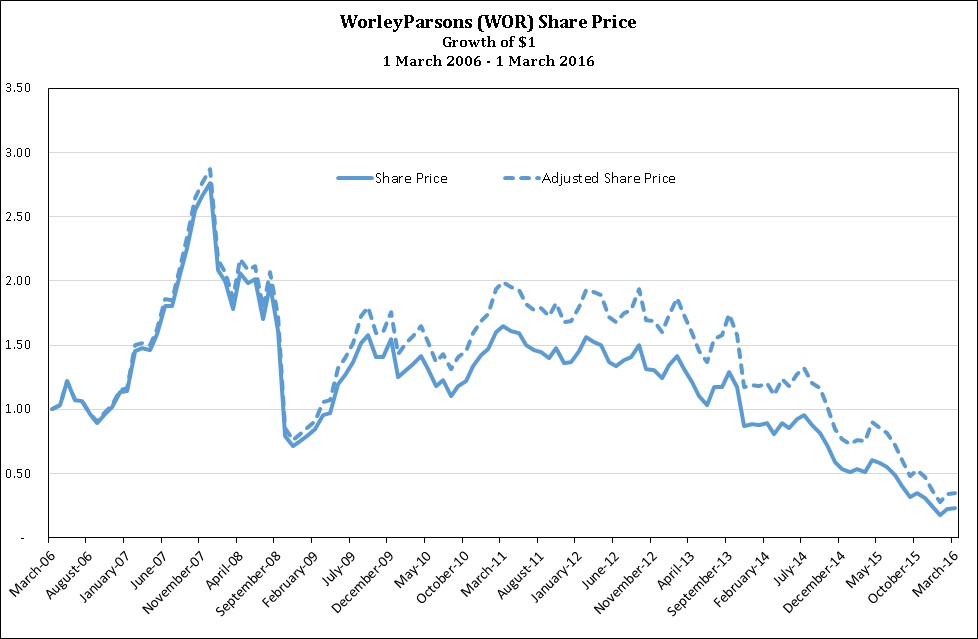

Over the past ten years, WorleyParsons has provided the opportunity to both make and lose a lot of money, as its fortunes soared with the resources boom and plummeted as the investment related intensity of that boom subsided. The chart below shows the 10 year history of the share price (based on the growth of a $1 invested on 1 March 2006) to 1 March 2016, both on a “price” and an adjusted (for dividends) basis. Its highest actual price over the period was $53.82 on 3 December 2007, with the lowest price of $3.11 recorded on 15 February 2016.

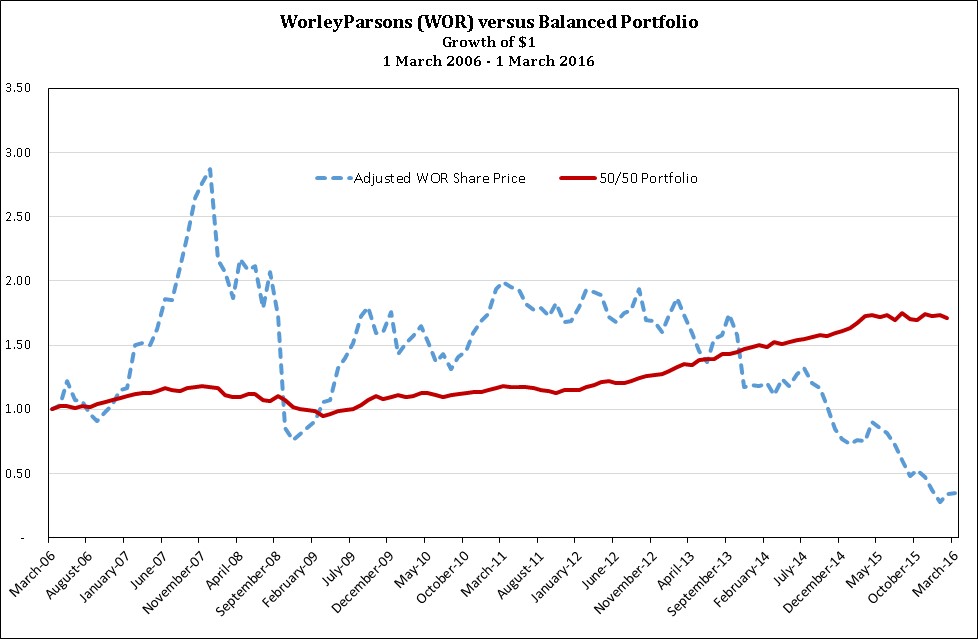

Contrast the WorleyParsons’ experience with that of an investor holding a highly diversified, typical 50% defensive asset/50% growth asset portfolio over the same period, as shown in the following chart:

The diversified portfolio looks like the slow boring tortoise that steadily gets the job done, through thick and thin, compared with the hyperactive WorleyParsons’ share bunny that over recent years appears to be in a death spiral and may expire before it reaches the finish line!

The best information doesn’t guarantee investment success

Many “investors” look at charts like the above and rather than see the volatility of an individual share as a threat, they see it as an opportunity. They believe they can hold concentrated share portfolios, successfully buying those shares that are on an upward trend and selling or avoiding those that are on the way down. And, they also believe the more they know about the particular company, its industry and general economic conditions, the more successful they are likely to be.

This view of the world would imply that company insiders, particularly directors and senior management, should be well placed to benefit from share price volatility, given their intimate knowledge of the company and the industry in which they work. However, in WorleyParsons’ case, the reality suggests otherwise.

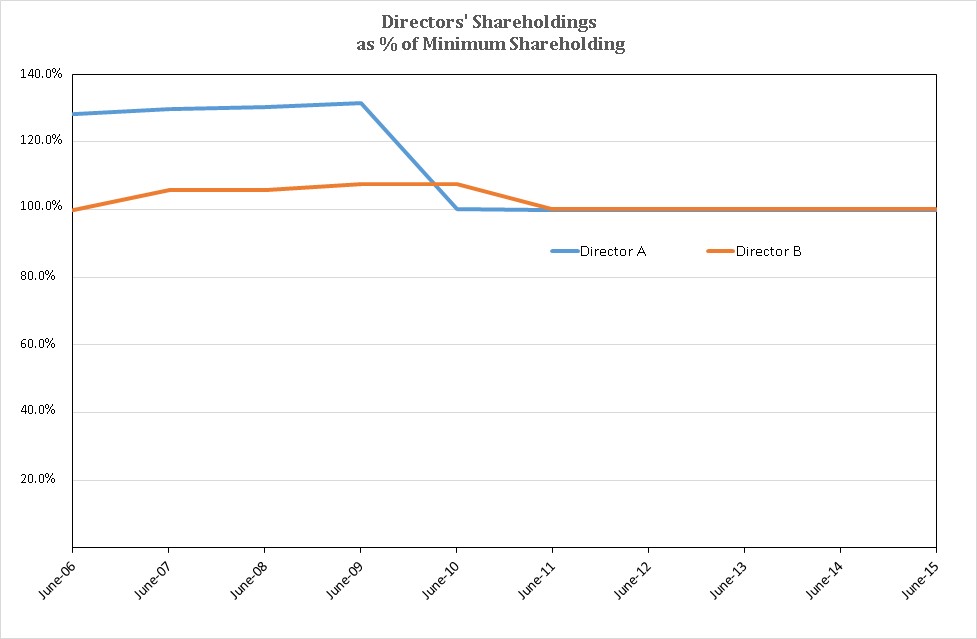

The chart below shows how the shareholdings of two directors (identified as Director A and Director B) that served over the entire period changed relative to their minimum holding. The only apparent voluntary changes in shareholdings occurred in the year ending June 2009, when both added modestly to their holdings, and in the year ending 30 June 2010 and 30 June 2011 when Director A and Director B, respectively, reduced their holdings. Since 30 June 2011, there have been no changes in shareholdings, despite a precipitous fall in the share price.

Now, clearly, directors are expected to show loyalty to their employer but you would think that if they thought they had any reliable market beating insights into the future of the company there would have been more share activity, consistent with the subsequent share price direction.

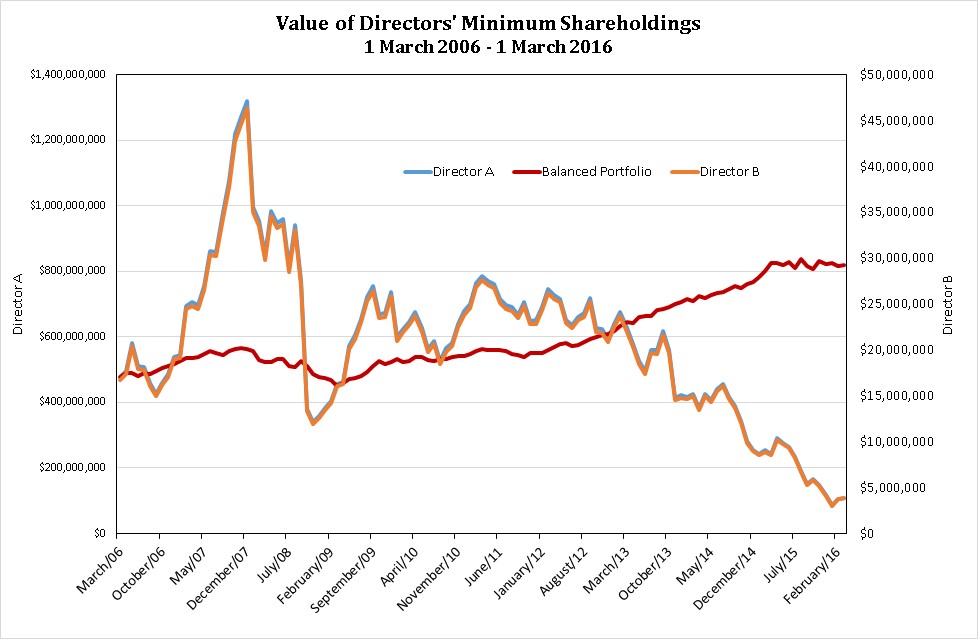

In the WorleyParsons’ situation, it wasn’t as if the directors didn’t have much at stake. The chart below shows how the value of their minimum shareholdings (Director A on the left hand axis and Director B on the right hand axis) fluctuated over the 10 year period, compared with had they invested the minimum holding at March 2006 in our balanced portfolio:

The personal wealth creation and destruction experienced by both directors is staggering. Did loyalty prevent them from reducing their shareholdings and prudently diversifying to protect their wealth or was it because they consistently and erroneously felt they knew more than the market, and still do?

The odds are against concentrated investing

Regardless, the WorleyParsons’ experience is a real world case study of the potential benefits and costs of making concentrated investment bets. At least for the period examined, for whatever reasons the best informed insiders initially made a lot of money but then proceeded to lose most of it.

Most investors have no informational advantage over the “wisdom of the market”. By choosing to take concentrated investment bets rather than building and sticking with a well structured diversified investment portfolio consistent with their appetite for risk they are, often unwittingly, playing “a loser’s game”.