Strong Aussie dollar wipes out international share gains …

In our recent article, “Should you hold international shares in your investment portfolio?”, we argued that there are diversification or risk reduction benefits from holding international shares as part of a share portfolio. To keep it manageable, we did not directly address the exchange rate risk that comes with owning shares denominated in another currency.

However, with the Australian dollar (AUD) appreciating 36% against the US dollar (USD) and 25% against the Reserve Bank’s trade weighted basket of currencies over the six months to September 2009, we are concerned that some poor decisions are being made in response.

The past six months has seen strong local currency gains in international shares almost completely offset by exchange rate losses when converted to AUD. This has resulted in some investor disenchantment with international shares. The knee jerk reaction has been to either reduce the international share allocation and/or to choose share funds that are protected against exchange rate movements i.e. hedged.

We think a permanent currency hedged exposure to international shares is a better alternative than changing allocations based on what the AUD has done or is expected to do. The latter is not investing – it’s exchange rate speculation.

But for serious long term investors, despite the immediate pain, we encourage you to ignore currency movements and maintain an unhedged allocation to international shares, based on an objective assessment of what is an appropriate long term asset allocation for you. In many cases, a strengthening AUD will imply topping up your international shares’ holding, rather than reducing it, to restore its previously determined weighting.

How do exchange rates affect returns on international shares?

Our view that you should ignore exchange rate movements when investing in international shares is based on the following:

1. Currencies are not investments. Long term, they have:

- an expected real (after inflation) return of zero; and

- no impact on the expected returns of international shares; and

2. Protection against currency movements (i.e. hedging) adds to investment costs. While hedging may provide peace of mind, it reduces expected long term after-tax returns.

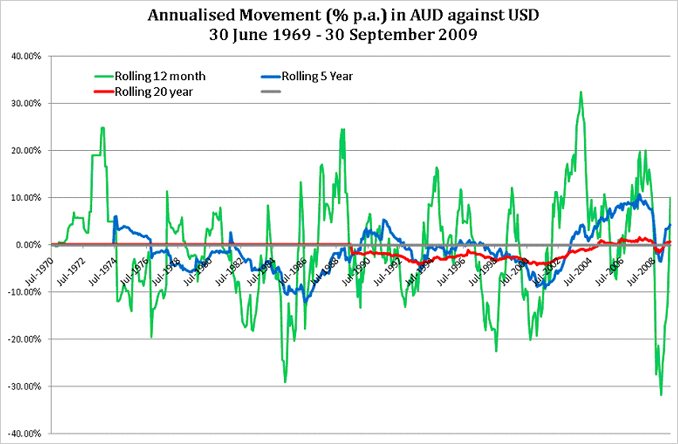

The first point is a little esoteric, but the following chart supports the argument. It shows the annualised movement in the AUD against the USD (it could have been any currency) for the following rolling periods:

- 12 months;

- 5 years; and

- 20 years

from 30 June 1969 to 30 September 2009.

It shows that over 12 monthly periods (the green line), exchange rate movements are extremely volatile, varying between plus and minus 30% p.a. for the period shown. Such swings can completely swamp local currency returns on international share investments.

For five years periods (the blue line), exchange rate volatility reduces considerably. But it still can massively affect the currency adjusted returns on international investments.

For the five years to July 1986, the AUD fell 12% p.a. against the USD, enhancing the return of US share investments when converted to AUD. Conversely, for the five years to October 2007, the AUD rose 10.7% p.a. against the USD, so that US share investments fared much worse in AUD than in USD terms.

But the key takeaway from the chart is that at 20 years (the red line), volatility largely disappears. For the 20 year periods ending 30 June 1989 to around March 2001, the AUD depreciated at about 2-4% p.a. against the USD. Most recently, no clear direction is evident.

Economists argue that over the long term, exchange rate movements must (largely) reflect actual and expected differences in inflation between countries. The long term AUD/USD exchange rate data shown above provides support for this view.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, Australia was and was perceived to be a high inflation country, relative to the US, resulting in a depreciating currency. But the past 20-25 years has seen differences in both actual and expected inflation narrow.

If exchange rates did not adjust for inflation differentials between countries, the prices of similar goods and services could vary purely due to inflation differences. But this creates incentives for international trade and exchange rate pressures consistent with restoring relativities. Eventually, either inflation differences will disappear and/or exchange rates must change.

Long term, then, exchange rate movements primarily serve to adjust relative prices between countries. They seem to do a reasonable job despite the fact that, short term, they could do anything. The serious investor understands the role of exchange rates and, accordingly, that currencies are not investments, they do not have expected long term real returns and they have no impact on expected risk adjusted, real returns of international shares.

Hedging your international shares costs real money …

Implied by the above discussion is the view that protecting your international share portfolio against exchange rate movements has no expected long term economic return. But it has certain costs.

At a minimum, there is the management time consumed in implementing the protection. There are also transaction costs in the form of foreign exchange spreads associated with purchasing and regularly rolling over the necessary forward foreign exchange contracts.

And, if your international share portfolio is owned by a tax paying entity, “successful” currency hedging could result in unexpected taxation obligations. When the AUD rises, a profit is made on the foreign exchange protection, equal to the fall in the value of the investment portfolio converted into AUD. This profit is treated as taxable income that cannot be offset by the unrealised loss on the underlying investment.

However, a fully hedged exposure to international shares does provide you with diversification benefits, as discussed in our previous article. If short term exchange rate volatility threatens your resolve to maintain long term investment discipline, perhaps the costs of hedging are worth bearing.

A half yearly update of the chart in this article is provided in our “Resources” area.

9 Comments. Leave new

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since losses are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, International shares: To hedge or not to hedge? […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] Despite no net currency movement over the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may take some time to claw back since “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This negative of protecting against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed further in our article, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]

[…] In spite of no net currency motion above the two years, the effect of hedging in this case is to bring forward tax payments that may possibly take some time to claw back given that “losses” are trapped in the trust structure. This damaging of safeguarding against currency exposure in managed international shares is discussed additional in our report, “International shares: To hedge or not to hedge?” […]