Markets react quickly to new information...

Research into transparent, actively traded markets such as share markets, foreign exchange markets and debt markets shows that prices react extremely quickly and efficiently to new information. And while prices at any point in time may not be “right” – whatever that means – it is reasonable to act as if the current price reflects all publicly available information.

The current price can therefore be confidently treated as the relevant market’s “best guess” of the value of a particular share, currency or debt instrument. This view of how markets work is known as the efficient market hypothesis and is a cornerstone of modern portfolio theory.

Also, because, for example, Woolworth’s current share price reflects all that’s publicly known about Woolworths, the only thing that makes its share price move is new information. Ahead of that new information becoming available, it is impossible to know whether it will affect the price positively or negatively. As news itself is essentially random, share price movements are also random and, as such, their future direction cannot be reliably predicted.

While the propositions that share prices reflect the market’s best estimate of current value and that their future direction is random are very simple, they are incredibly powerful. In particular, they have massive implications for the validity and worth of common investment practices.

Active funds management ranks with astrology...

Active funds management is the attempt to outperform market benchmarks using such techniques as fundamental analysis (or “stock picking”), technical analysis (or “charting”) and market timing. It contrasts with passive funds management, where the manager constructs an investment portfolio to mirror the relevant asset class benchmark – no subjective stock picking or market timing is involved. The aim is to deliver the “market” return, less relatively minimal cost.

The “markets work” view of the world considers that the techniques of active fund managers have about as much validity as astrology and fortune telling. The techniques and their flaws are discussed below:

Fundamental analysis, or stock picking, is the attempt to identify mispriced shares (i.e. undervalued or overvalued shares) by examining historical financial information of companies, often supplemented by interviewing company executives. Based on information already in the market, the analyst makes predictions regarding changes in the relative values of companies, with the purpose of buying those shares that are regarded as relatively “cheap” and avoiding, or sometimes selling, those regarded as relatively expensive.

Effectively, the analyst is saying that 1) the market’s got it wrong and 2) it will eventually wake up and see things as the analyst does (before any new information makes the analysis redundant). We, and most of the leading finance researchers, think these premises are unsound. The analyst can never know as much as the market. He/she just doesn’t know what they don’t know. And, even if the analyst is right, there is no guarantee the market will ever respond accordingly.

Despite its flawed foundations, stock picking remains the core “value add” claimed by most active share or equity fund managers. While many of these people still bow down to the father of fundamental analysis, Benjamin Graham, co-author with David Dodd of the 1930’s classic “Security Analysis”, they prefer to ignore his view expressed just prior to his death in 1976:

“I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity, say, 40 years ago when Graham and Dodd was first published; but the situation has changed…. [Today] I doubt whether such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their cost…. I’m on the side of the ‘efficient’ market school of thought.”

Technical analysis or charting seeks to identify trends or patterns in past prices in order to predict future prices. Chartists seem to think that prices have some sort of memory. However, if current prices reflect all available information, as the efficient markets hypothesis proposes, then future prices are unrelated to or independent of past price changes. While the research suggests there is some evidence of dependence of future share prices on past prices (i.e. a feature called “momentum”), it also reveals that this effect is difficult to profitably exploit and refutes any validity for the usual forms of charting.

Market timing advocates adjusting your investment holdings to benefit from predicted changes in relative prices of shares, market sectors (e.g. switch from resources shares to financial shares) or asset classes (e.g. reduce share allocation and increase weighting to cash). It relies on being able to predict the future, either using a trend following technique (i.e. charting) or economic forecasts. Like “stock picking”, market timers are saying there are mispricings that can be reliably taken advantage of and, like stock pickers, they think they are smarter than the market.

Smart people are the market...

But all these smart people are the market. The irony is that markets “work” and are “efficient” because there are so many smart people out there who believe they can “beat the market”. Their competition and diligence ensures that it is very unlikely that any of them will actually do so, with reliability. Any opportunities for easy wins will quickly be exploited and disappear. Most outperformance will result either from luck or by taking greater risk compared with that of the relevant benchmark.

While all this is not music to the ears of the active funds management industry, it is very good news for you, as an investor. You don’t need to work out whether the share you would like to buy or sell is priced appropriately for its level of risk – you are better off operating on the assumption that the market has already done that for you and the current price is the best guess of value. You can buy or sell as confidently as the most seasoned professional knowing that the price you pay or receive is “fair”. In other words, no investor can expect to receive greater returns without bearing greater risk.

The evidence does not support active management...

What’s the evidence that markets work, as discussed above. Well, it’s pretty strong, but the researchers have shown there are a few anomalies that should not exist if markets were truly efficient. However, none of the anomalies that have been discovered appear to be able to be profitably exploited.

But more relevant to the real world of investing, if markets were not workably efficient (or “fair”), a couple of things that you would expect to see are:

To cut to the chase, the robust academic research consistently demonstrates that active fund managers do not reliably outperform properly constructed benchmarks and that apparent fund manager skill is evident less often than you would predict just by pure chance. Rather than discuss this research in detail, a couple of less than rigorous illustrations of what should be damming evidence for active fund management are discussed below.

The evidence does not support active management...

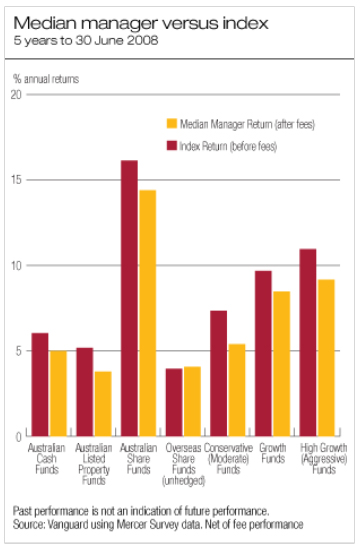

It compares the performance of the median (or middle ranking) active fund manager with its relevant benchmark for each of the identified asset classes for the five year period to 30 June 2008. Other than for “overseas share funds”, it shows that the middle ranking active fund manager underperformed their benchmark.

Now this is not robust research. The period is too short, the data is flawed and Vanguard, as a passive fund manager, has a vested interest in the result. But it is what simple arithmetic would expect you to see. If passive fund managers receive asset class returns less relatively small costs, then all active fund managers (since they make up the bulk of the remainder of the market) will receive asset class returns less their relatively high costs.

It is impossible for all active fund managers to outperform their relevant benchmarks, but their promotion suggests that they all expect they will. Their advertising would be more truthful if it said “While we hope to outperform our benchmark, on average active fund managers for our relevant asset class can expect to achieve a return equal to that of the benchmark less our average costs”. Of course, such truthfulness could result in the severe shrinking of a massive industry that cannot, in total, deliver on its fundamental proposition of “beating the market”.

The chart below is taken from Vanguard Australia’s web site.

Where is the Tiger Woods of active funds management?

Having had the arithmetic of investment markets explained, most people concede that all professional active fund managers cannot outperform their asset class benchmarks. However, many feel that they are capable of reliably selecting those fund managers that will outperform in the future. And if investment management was a truly skill (rather than luck) based activity, their thinking would have some validity.

But the robust evidence suggests that genuine skill in investment management is a rarity. A simple analogy is illustrative. The chart below shows the top three ranked professional golfers for various years from 2000-2007.

2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2007 |

| 1. Tiger Woods | 1. Tiger Woods | 1. Vijay Singh | 1. Tiger Woods | 1. Tiger Woods |

| 2. Phil Mickelson | 2. Vijay Singh | 2. Ernie Els | 2. Jim Furyk | 2. Ernie Els |

| 3. Ernie Els | 3. Ernie Els | 3. Tiger Woods | 3. Adam Scott | 3. Justin Rose |

In golf, skill prevails – as long as they are healthy, the top ranked golfers remain at the top. It is inconceivable that Tiger Woods could rank Number 1 in 2002 and drop to Number 300 in 2004. Questions are asked regarding his failing powers if he even drops to Number 3. If it is the end of 2007 and you are betting on who will be the top ranked golfers in 2008 (assuming they remain healthy) then, as in all genuine skill based activities, the past is a good guide to the future.

But we do not see the same consistency (or persistence) in investment management. The table below, with all its simplicity and flaws, illustrates the point. It shows the top three ranked Australian wholesale equity managers from Morningstar data for the same years as for the golf rankings above.

2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2007 |

| 1. RCM (-) | 1. Sandhurst (44) | 1. Ausbil (9) | 1. AMP Capital (19) | 1. ING (-) |

| 2. Alpha (-) | 2. Souls (1) | 2. Dimensional (3) | 2. Perpetual (-) | 2. Hunter Hall (-) |

| 3. Advance (67) | 3. Perpetual (5) | 3. Perpetual (8) | 3. Hunter Hall (-) | 3. Macquarie (36) |

Number in brackets are ranking out of 72 for 7 years to December 2007. (-) implies no 7 year history.

Unlike the golf example, different names emerge each year. And the most common name, Perpetual, with three mentions, represents three different funds. Performance in any one year is not, apparently, a good indicator of performance over the full seven year period – Advance ranked third in 2000 but 67 out of 72 for the 7 years to December 2007.

Sure, Soul and Dimensional ranked well in 2002 and 2004, respectively, and over the entire period. But given the performance ranking spread of other managers over the eight years, was this due to skill or luck and does it say anything about the future? And, interestingly, Dimensional is a passive funds manager so its result cannot be used by apologists for active fund management!

How many times have you seen investment ads touting recent performance, with the small print warning “Past performance is not indicative of future performance” hidden down the bottom? In our view, the warning should be given the same prominence as the “Smoking is a health hazard” messages on cigarette packages, as failure to heed it can have very serious consequences for your financial health.

Don’t fight the market

Markets work to allocate investment capital to where it will earn its highest expected return for risk taken. While with the benefit of hindsight this is not always the actual outcome, there is no evidence to indicate that active fund managers can reliably “second guess” the market. However, their efforts ensure that most investors will be better off patiently letting markets work rather than allocating valuable resources trying to outguess them.