How important is the timing of you retirement?

How important is the timing of you retirement?

There have been numerous studies done over recent times about the cost of retiring at the wrong time. As investors, we need to manage the balancing act of taking on enough risk to maintain our purchasing power, but not too much that it jeopardises our affairs.

Over the long term, we expect to be rewarded for the investment risk we accept. However, these rewards do not appear evenly over time. And the order in which the returns appear can have a dramatic impact on your portfolio’s survival.

In simplistic terms, a retiree who experiences low returns in the early years of their retirement has a higher chance of running out of money, (even if these are followed by good returns in the latter years), compared to a retiree who experiences good early returns. The implication is that anyone who retired in 2007 (just prior to the GFC) is extremely unlucky and is an isolated case of retirement timing disaster.

While the timing of your retirement does have an impact, the reality is that it’s not quite as cut and dry as implied by some analysis.

The order of returns does matter but …

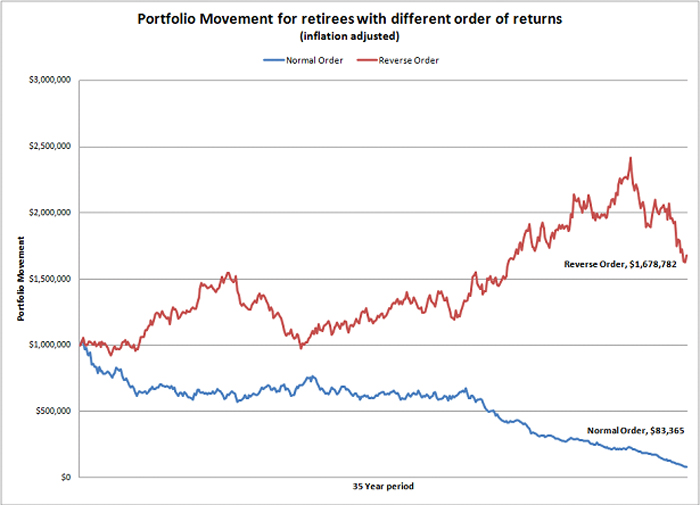

Let’s look at a theoretical example of two retirees living in parallel universes. Both have $1 million in investment capital and need $50,000 per annum (indexed to inflation) to meet their retirement requirements.

Over the next 35 years they both adopt a growth oriented portfolio [1] structure and receive an identical annualised return of 5.26% (after inflation). The only difference is that in one universe the order of the monthly returns is reversed.

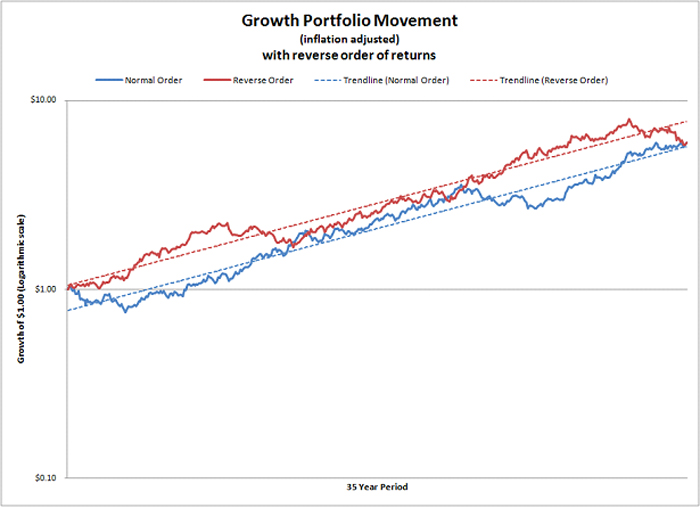

Let’s first look at a chart showing the growth of $1.00 invested in each portfolio.

All distributions are reinvested and there are no additions to or withdrawals from the initial investment amount.

The initial $1.00 investment ends up growing to $6.01 by the end of the period, even though the paths are quite different. This reflects the fact that each portfolio earned an (inflation adjusted) return of 5.26% per annum over the 35 year period. The parallel trend lines confirm identical rates of returns.

But, what happens when we apply these portfolio returns to their actual situations with an initial investment of $1 million and annual drawings of $50,000.

Under these circumstances, one retiree has a vastly different experience than the other. The retiree with poor early returns suffers.

Such examples are often used to support the proposition that anyone who retired in 2007, just prior to the GFC downturn, would be significantly worse off than a retiree who retired (say) 5 years earlier or 5 years later. But, is that really the case?

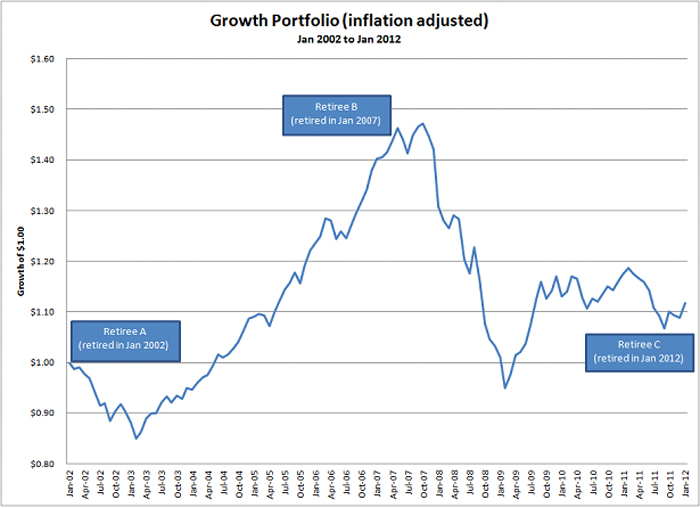

The chart below shows the performance of markets over the last 10 years for an (inflation adjusted) growth portfolio. If you had to choose between the three retirees (A, B or C), which would you prefer to be?

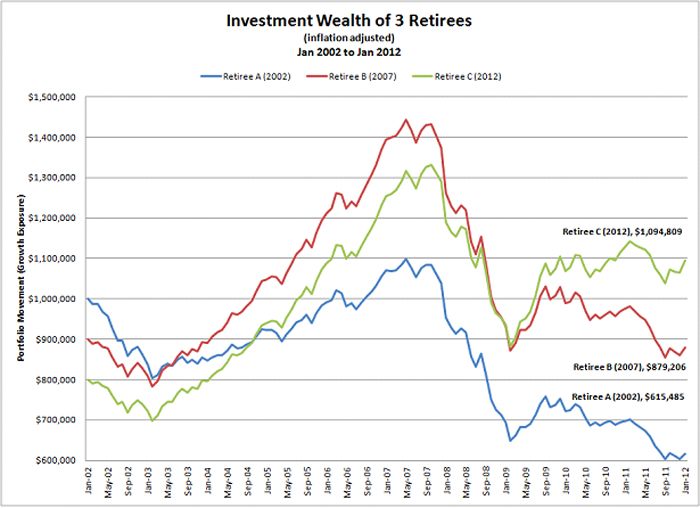

Clearly, Retiree B has the worst initial returns and by implication they should fare the worst of the three. However, when we include the fact that each retiree has participated in the same ups and downs of the market we get a different picture. Our comparative assessment [2] shows the path of each retiree’s investment wealth over the last 10 years:

The table below reveals that it’s not obvious which retiree is in the worst position as at January 2012.

| Retiree | Retirement Investment Capital | Remaining Years of Retirement |

| Retiree A | $615,485 | 25 years |

| Retiree B | $879,206 | 30 years |

| Retiree C | $1,094,809 | 35 years |

It’s certainly not obvious that Retiree B is the only unlucky one.

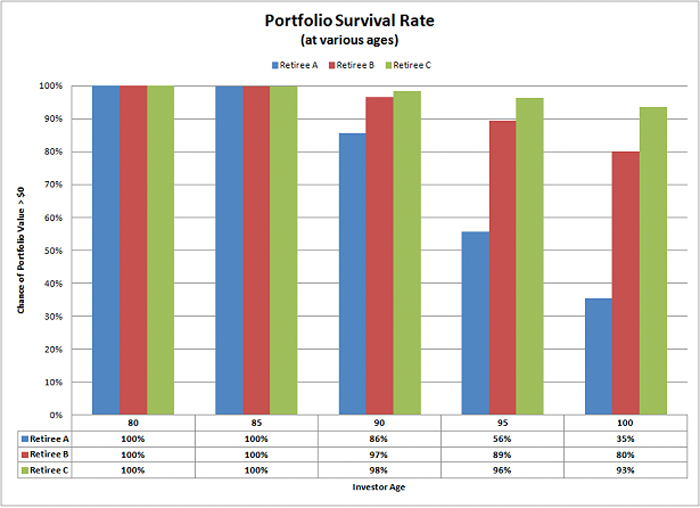

Using the above positions, we assessed the portfolio survival rate of each retiree (using a Monte Carlo simulator) and found that of the three, Retiree A had the greatest chance of running out of money.

Interestingly, the portfolio survival rate of Retiree B is not that much worse than that of Retiree C. This would seem to contradict the findings of many of the studies on this topic.

Poor market returns affect all investors

It’s important to do assessments in isolation of other variables to identify the impact of key drivers, such as the effect of the sequence of returns. However, care needs to be taken in drawing broader implications from these studies.

Unfortunately, many recent retirees have been left with the impression that they’re somehow much worse off than their fellow retirees. The fact is that the GFC has hurt all investors, some more than others, and the relative impact of retirement timing has been grossly over stated.

While it’s important for investors to consider their financial position in an absolute sense (e.g. in terms of their portfolio survival rate), psychologically this can lead to a feeling of being separately affected by investment trends. This tends to lead investors towards over optimism in good times and over pessimism in tough times. From our perspective, a bit of relativity helps.

[1] This growth oriented portfolio is made up of the following allocations – 20% to Cash, 5% Australian Bonds, 5% to International Bonds, 10% to Listed Property, 35% to Australian Shares and 25% to International Shares. [2] We assume a retirement period of 35 years for each retiree. Retiree A had $1 million of investment capital at their retirement in 2002. Retiree B had $900,000 invested in 2002 and invested a further $100,000 before their 2007 retirement and Retiree C had $800,000 invested in 2002 and invested a further $200,000 before their 2012 retirement. Each draws an inflation adjusted $50,000 per annum from their portfolio in retirement.