Rentvesting: a cheaper way to own a home?

Before attempting to answer the question posed by the title of the article, it may be necessary to explain what “rentvesting” is. Essentially, it involves purchasing a residential property to rent to a third party while, at the same time, renting another property to live in.

It’s the mechanism that many young (and some not so young) adults are using to get a foothold in increasingly less affordable housing markets, particularly in Melbourne and Sydney. Many property spruikers, who previously would have used the old chestnut that “rent money is dead money” to promote residential property purchase, now promote rentvesting as a smart way to rent and buy property.

But does rentvesting make financial sense? We have identified at least three approaches to rentvesting, making it difficult to generalise. The three approaches are:

- You rent where you want to live and buy for rental what you can afford – generally, the investment property is in a less desirable/ less expensive area than where you wish to live. The primary motivation for this behavior may not be to save money, but simply to get into the property market;

- Purchasing and renting out a property you would like to live in but can’t afford, and renting something cheaper to live in or, often, living with parents – again, the primary motivation is to get into the property market but there is also an expectation of saving money; and

- Less often seen, but offering a more pure situation to examine the pros and cons of rentvesting compared with owner occupation, is purchasing a residential property to rent to a third party while at the same time renting a comparable property to live in.

We look at the economics of the third alternative in the rest of the article. The other alternatives described above are variants of this like for like comparison.

Rentvesting versus owner occupation

We assume the property (a 2 bedroom apartment) purchased for rent or owner occupation costs $1.2 million. As a rental property, it has an initial gross yield of 3.3% p.a. (i.e. rent of $39,600 p.a.). A deposit of $200,000 is available, implying a borrowing requirement of $1.0 million. The interest rate on the loan is 5.0% p.a., both for investment and owner occupation purposes.

Property costs common to both investment and owner occupation (e.g. strata fees, maintenance, rates etc.) are 13.0% of annual rental, (i.e. $5,148 p.a.), with purely investor related costs (e.g. property management fees, tax and administration costs) assumed at 8.0% of annual rental (i.e. $3,168 p.a.). It is also assumed the investor can claim depreciation of 1.0% p.a. of the initial value of the apartment (i.e. $12,000 p.a.).

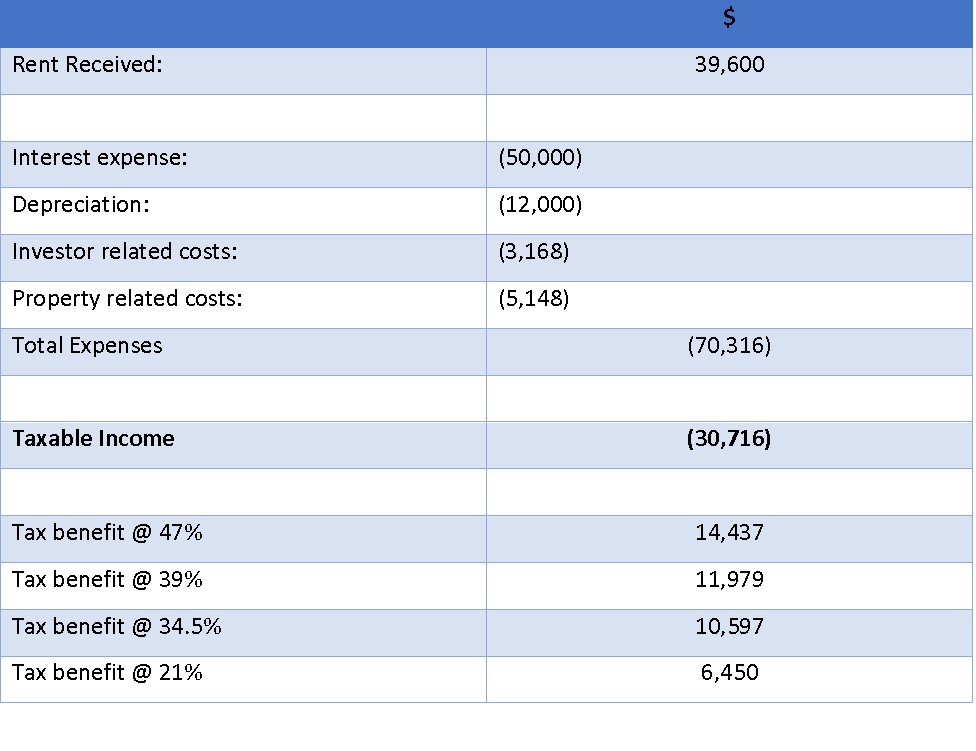

The table below shows the potential first year’s tax calculations for the investor, together with the resulting tax benefit for the various marginal tax rates (plus Medicare Levy):

It reveals that the taxable income loss provides the investor with a significant cash tax benefit, that increases with the investor’s marginal tax rate.

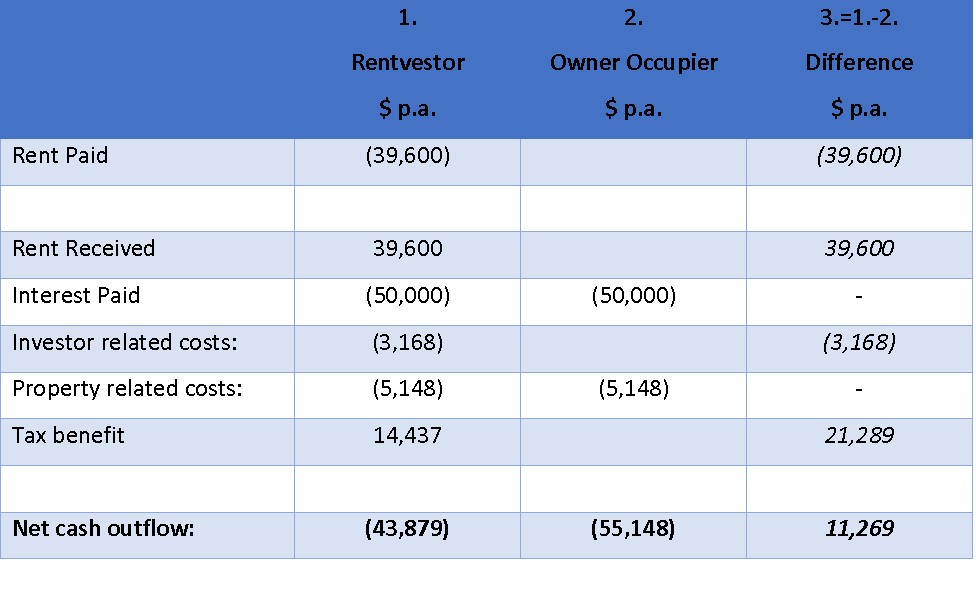

Next, the following table compares the first year expected cash flows for a rentvestor (who purchases the apartment, rents it out and then rents a comparable property) with a marginal tax rate of 47% with those of an owner occupier (who purchases the apartment and lives in it):

The far right column shows that for this example the rentvestor is $11,269 (or about 0.9% of the value of the apartment) better off in the first year than the owner occupier, indicating that rentvesting is a potentially cheaper way to obtain home ownership than actually living in the home you buy.

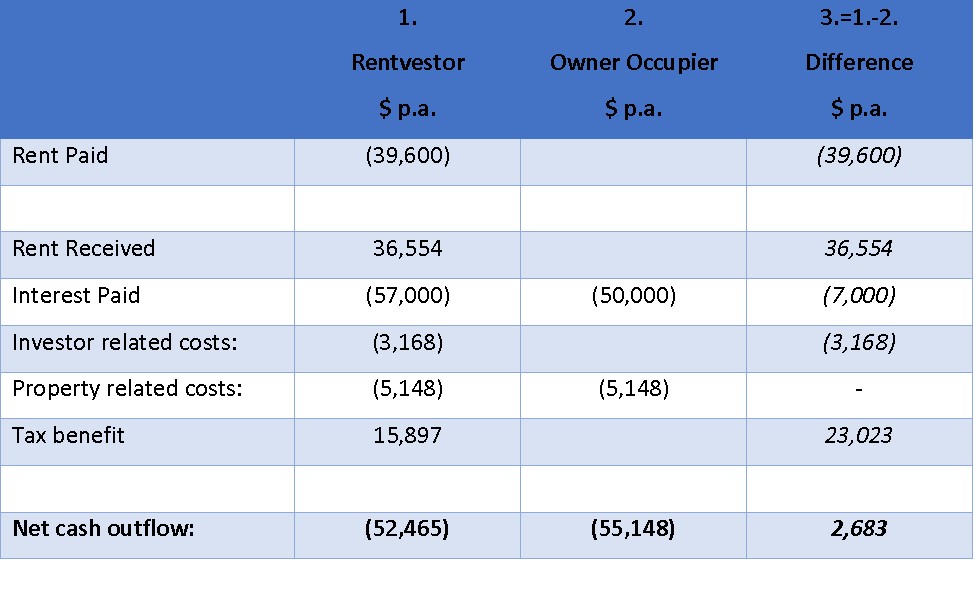

But even ignoring the different capital gains tax treatment that applies to the sale of an investment property versus your principal residence, it doesn’t take too much to undermine the above analysis. For example, the reworked table below assumes a 39% marginal tax rate investor (more typical for young adults attracted to rentvesting), a 7.7% vacancy rate (i.e. 4 weeks a year) and a 0.7% premium for investment loans compared with owner occupier loans (typical of recent market trends):

The rentvesting financial advantage reduces to only $2,683 (or 0.2% of the value of the apartment), with the rentvestor also subject to the typical uncertainties of any renter (i.e. uncertainty of tenancy, variable property management performance etc.) not faced by an owner occupier. A somewhat marginal proposition!

Just renting may be the sensible alternative

The relatively recent phenomenon of rentvesting is driven by the combination of declining housing affordability and negative gearing (i.e. the ability to claim excess tax deductions associated with property rental against other income).

It is a potentially cost effective approach to home ownership. But our concern is that many young (and some not so young) adults are being seduced into a highly compromised home purchase alternative they really can’t afford by the lure of tax benefits, that can quickly be eroded by other elements of the rentvesting strategy.

If unaffordability is the issue, the lower risk and lower initial cost alternative is to simply rent. For the example above, and assuming a 2.5% p.a. interest return on the property deposit, cash outflow in year 1 would be $36,550 – a $15,915 saving on rentvesting. Admittedly, unpalatable for those who are convinced that Australian house prices will only ever go up.