The key decision is your defensive versus growth allocation

It is a key element of our approach to investment risk management that you should select a target asset allocation that is consistent with your attitude to risk (i.e. a level of investment risk that will enable you to “sleep well”, regardless of what investment markets are doing). The target is to be met at or before your desired retirement date and/or by the time you wish to be financially independent (i.e. have sufficient investment wealth to support your desired lifestyle, without the need to work).

The target asset allocation is primarily focused on your mix of defensive assets (i.e. cash, fixed interest) and growth assets (i.e. primarily, Australian and international shares, and property). If the current defensive/growth allocation varies from target, we work with clients to develop and implement a strategy to transition over time from where they are now to that target.

We also agree with clients how they allocate the growth component of their investment portfolio between the primary growth asset classes i.e. Australian shares, international shares and property. While this allocation decision is both part art and part science, most investors (both in Australia and around the world) tend to have a strong “home company bias” i.e. Australian investors tend to heavily overweight Australian shares and property, despite our markets only being a small percentage of global share and property markets.

Once that decision has been made and the chosen allocation put in place, a consequent issue is how should the growth portfolio be rebalanced given that the allocations will be constantly changing as values of the component parts move and often in opposite directions. The rest of this article examines this rebalancing question.

We examine three (of many) approaches to growth asset rebalancing

For purposes of our analysis, we examine a reasonably typical growth portfolio over the 35 year period from 31 December 1981 to 31 December 2016. Its initial composition is as follows:

- 40% Australian shares[1];

- 40% international shares[2]; and

- 20% property, in the form of listed real estate investment trusts[3].

The most extreme approach to rebalancing, that is advocated by some “efficient market” purists, is to never rebalance as the market is considered the best judge of the value of the underlying securities that make up the asset classes. This view sees rebalancing as a form of market timing that does not reliably add value.

Also, a clear benefit of not rebalancing is that the associated transaction costs and potential crystallisation of tax liabilities associated with actively changing a portfolio’s composition are avoided.

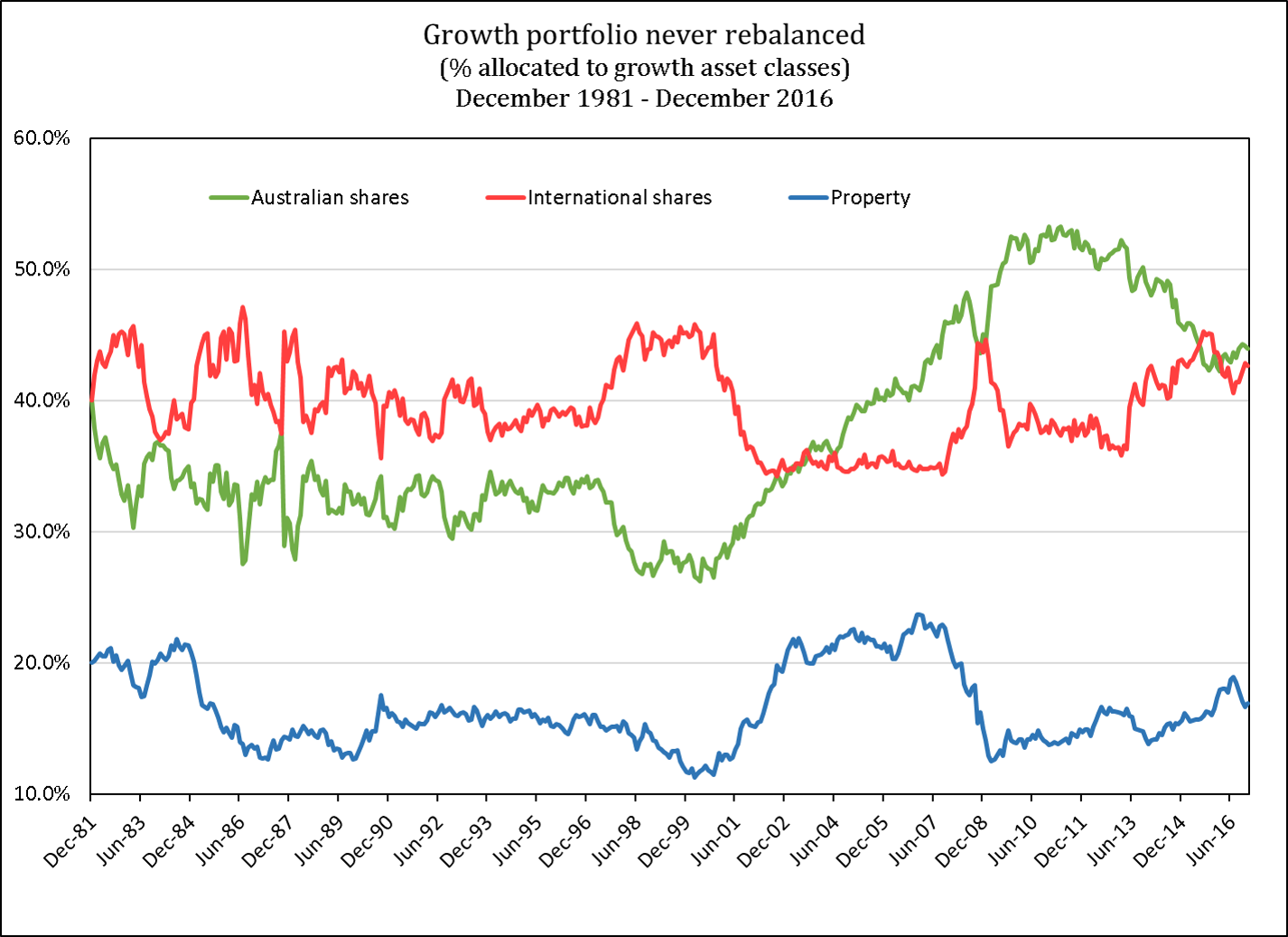

The chart below reveals the significant variations from the initial growth asset allocation resulting from a decision to never rebalance:

Australian shares fell to as low as a little over 26% of the portfolio during the “tech stock” boom in the late 1990’s, before rising to a peak of about 54% at the height of the mining boom. It is unlikely that Australian investors, with their strong “home country bias”, would have been particularly comfortable with a growth portfolio comprising only 26% Australian shares and less than 12% Australian property, implying a 62% international share-holding, regardless of the validity of the efficient market view.

It is interesting and, we think, not a complete surprise, that by the end of the 35 year period the asset allocations were not too far off their starting points, despite the significant variability within the period.

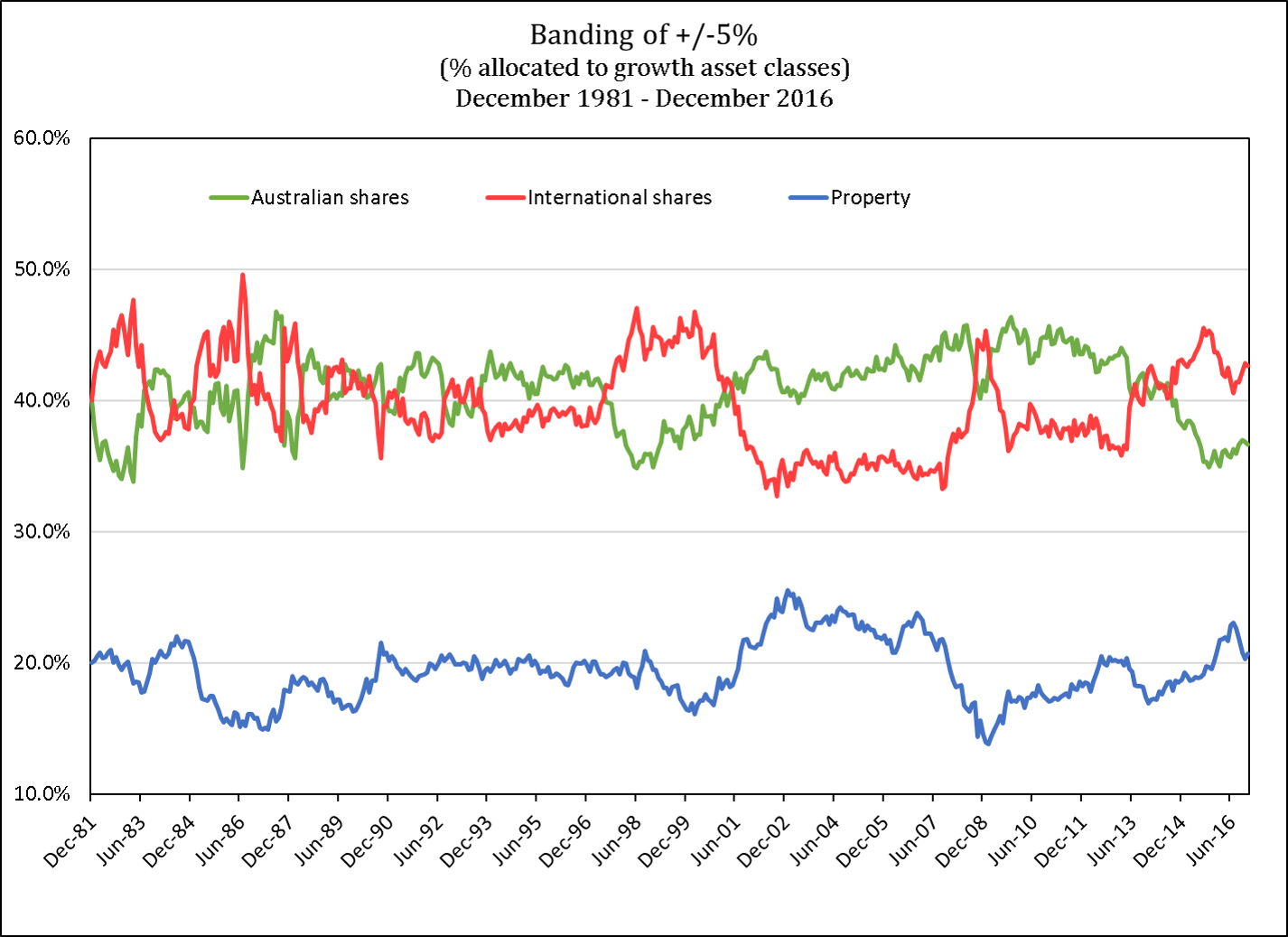

An alternative approach to never rebalancing is to not let the asset allocation go outside previously determined bands, above and below the initial allocations (we shall call this “banding”). A rationale for such an approach is based on a view, unsupported by academic research, that the performance of asset classes tends to trend upwards and downwards, before reverting to the mean. By allowing allocations to deviate within a pre-determined range, “banding” aims to keep the investor more exposed to rising asset classes and less exposed to falling asset classes, compared with regular, time based approaches to rebalancing.

Banding also generally involves less transaction costs than more regular and frequent rebalancing approaches.

The chart below shows how allocations changed over the 35 year period, assuming bands of +/- 5% from the initial asset allocations:

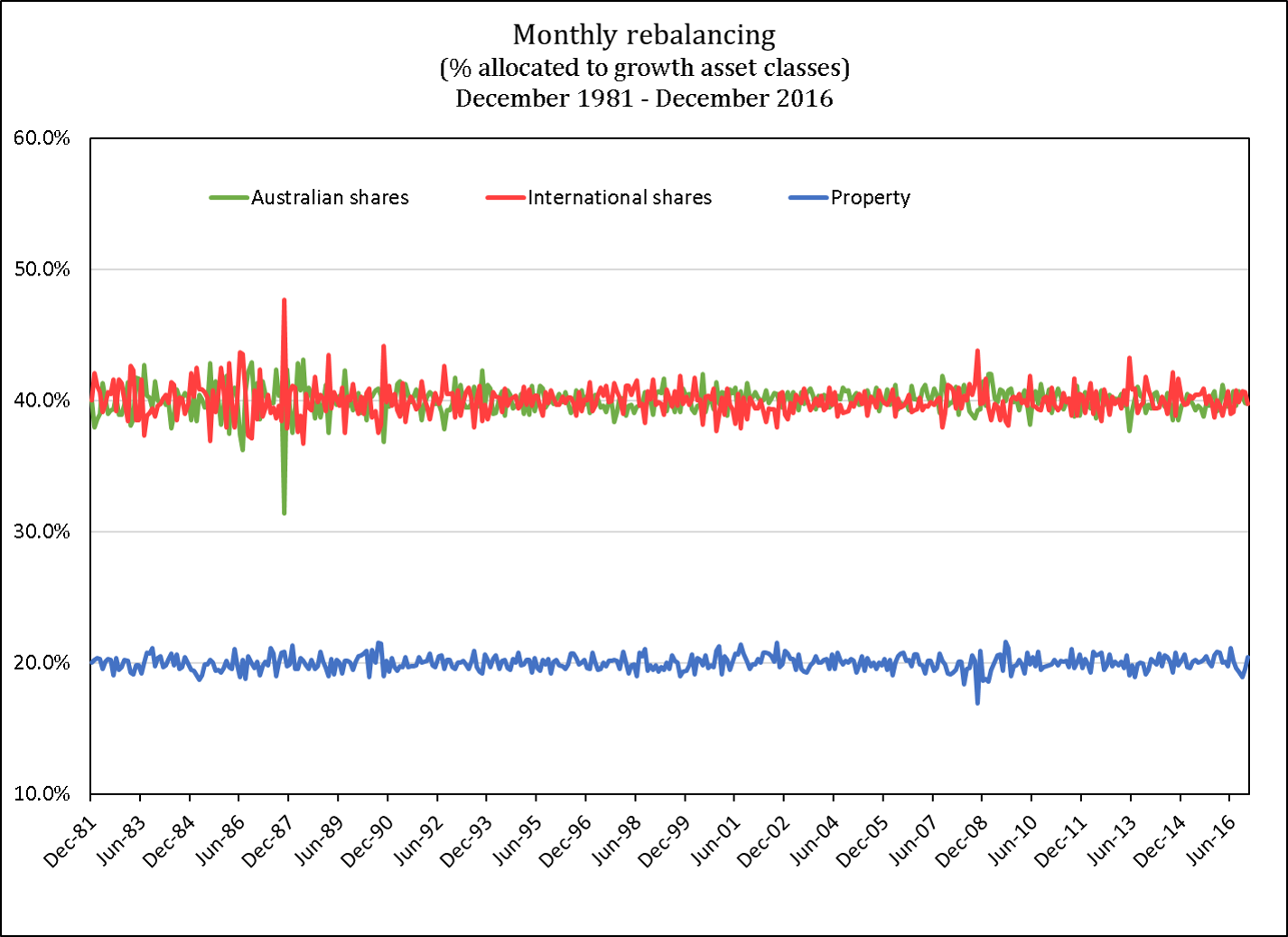

A final approach to rebalancing that we examine is regular, time based rebalancing back to the initial allocations. The chart below assumes monthly rebalancing, purely for illustrative purposes:

The close adherence to the initial allocations almost certainly comes at the expense of higher transactions costs compared with no rebalancing and banding.

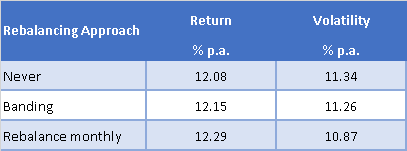

Which approach is better? For our examples, the table below shows the annualised returns and volatility measures for the three approaches for the 35 year period:

Monthly rebalancing resulted in the highest return, at the lowest volatility. A clear winner?

Not really, as the returns are before transaction costs and taxes. And the differences in returns and volatilities are not large enough to be confident that they would apply regardless of the bands or rebalancing periods chosen, either historically or in the future.

We take a pragmatic, disciplined approach to growth asset rebalancing

With no clear winner evident, we tend to take a pragmatic approach to rebalancing. We reject the “no rebalancing” approach because of its conflict with the “home country bias”. A strict banding approach is based on arbitrary bands and its return enhancement claims are not supported by the robust evidence.

We tend to review portfolios for potential rebalancing no more than every three months (to reduce transaction costs, compared with monthly rebalancing) and will not rebalance unless there are significant divergences from target allocations. In the event there are significant divergences, we generally transition to the targets progressively, rather than in one-off increments.

Our approach is as much about implementing discipline and taking advantage of the risk reduction benefits of broad diversification, both within and across asset classes, as it is about relying on rebalancing to achieve the “best” risk efficient returns.

[1] As measured by the S&P/ASX 300 Index (Total Return)

[2] As measured by the MSCI World ex Australia Index (net div., AUD)

[3] As measured by the S&P ASX300 A-REIT Index (Total Return)