Evidence triumphs over anecdote

If you’ve seen the movie “Moneyball”, (or read the book by Michael Lewis), you may have picked up on some similarities between the issues faced in managing a major league baseball team and those faced in managing investment wealth.

If you’re not familiar with the movie/book, it tells the story of Billy Beane, a professional baseball manager of the Oakland A’s, a low tier baseball team in the US major league. To overcome the financial power of the top tier teams, he adopts an approach that focuses on buying the attributes that win games (rather than buying the specific players he thinks will win games).

Rather than replace a high profile, big hitter with another equally expensive big hitter, Beane looked for other ways to replace him. The team didn’t necessarily need another big hitter, they needed to replace the (statistical) attributes that they had lost (e.g. the average number of times he got on base per game). By looking at player selection in this way he gave himself the freedom to build a winning baseball team without the restrictions imposed by traditional methods.

Subjective biases often conflict with objective evidence

We are all predisposed to behavioural biases that can get in the way of achieving the outcomes we want. These include:

- Our desire for conformity and following the crowd (regardless of how irrational that activity may be),

- Our natural inclination to take mental shortcuts, leading us to focus on subsets of available information, ignoring the whole. We generalise from personal experience and extrapolate (too readily) from recent events, and

- Our uncanny ability for self deception. We are far more likely to attribute positive outcomes to skill and negative outcomes to bad luck. This self deception results in a level of overconfidence that is unwarranted.

Beane takes on the established ways of the baseball scouts who have spent most of their lives in the pursuit of discovering the next super star. Their primary focus is on athleticism, hitting power and demeanour but also extends to upbringing, looks and even girlfriends. The decision by one scout to discard a player is driven by the rating of his girlfriend: – “She’s only a 6 – it’s a sign of low self confidence”. These subjective factors are all tossed around until some sort of consensus is achieved.

Beane knows the folly of this approach. He was once one of those “discovered super stars” who met all the criteria of the scouts. Yet, he never lived up to their high expectations. He knows their approach is littered with behavioural biases that cannot help his team.

He (or at least his assistant) has researched baseball history (statistics) and knows how many runs are needed to win enough games to play in the finals. His aim is not to buy players, it’s to buy runs. And, buying runs is cheaper than buying players.

The research found that “an extra point of on-base percentage was worth three times an extra point of slugging percentage. A player’s ability to get on base especially when it was in unspectacular ways tended to be dramatically underpriced in relation to other abilities.”

As you’d expect, Beane’s non-conformist approach ruffles feathers and leads to many fall outs with staff and players. Biases and beliefs are hard to shift.

“Moneyball” highlights a level of self deception amongst the scouts (and the general baseball community). They spend a lot of time “researching” their targets and insist they can tell the difference between hitters, yet “one absolutely cannot tell, by watching, the difference between a .300 hitter and a .275 hitter. The difference is one hit every two weeks”. Still, conformity wins out. This behaviour has been pervasive for decades.

Interestingly, Beane had no issue in divulging his approach to Lewis for the book. He did not see it would jeopardise his edge. He believed the behavioural irrationalities are so ingrained they will never disappear.

The “Moneyball” story has clear investment parallels. Stock brokers and investment pundits have the most intimate knowledge of their most prized stock tip, yet have no real evidence that it is not already overpriced. Many investors seek the comfort of blue chip shares. They look good and have great (apparent) prospects but if everyone else wants them they come at a pretty high price.

Value stocks on the other hand are out of favour. No one really wants them and consequently you can purchase them (relatively) cheaply. Sure, there’s more risk but if you hold a diversified exposure of value stocks, they’re more likely to outperform the blue chips.

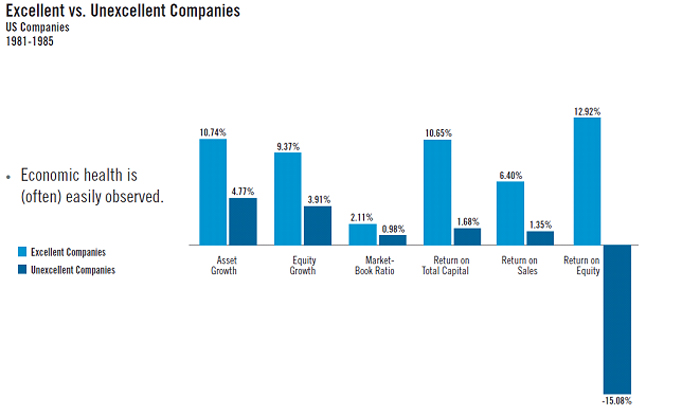

Many investors would question the rationale of buying a company that has poor prospects? Viewed objectively, though, the higher risk prospect has a higher expected rate of return. Michelle Clayman illustrated this concept in 1987 when she compared “Excellent” companies, identified by the 1980s best seller, “In Search of Excellence”, with a selected group of companies regarded as “Unexcellent”. The comparative economic health measures that distinguish the companies are as shown below:

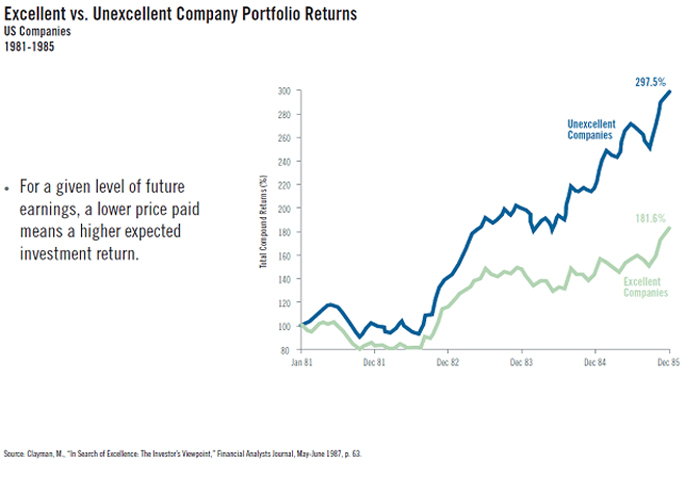

Despite appearing unattractive, in the five years that followed the publication of the book, the return on the shares of the Unexcellent companies exceeded that of the Excellent companies by a wide margin.

Do you want to buy quality players (excellent companies) or buy the most runs you can afford within your budget (maximise the return for your risk budget)?

Our greatest challenge is often us

In applying the observations of “Moneyball” to wealth management, it would appear that our greatest challenge to improving outcomes is in overcoming our behavioural biases.

Often we get caught up in the excitement of a share or financial product that has sound “pedigree” and great prospects. Yet, we miss the bigger picture of how it fits in to a lifetime plan. Further, many investment strategies miss the mark by focusing (almost exclusively) on high returns (i.e. big hitters) instead of on maximising the chances of achieving long term objectives (i.e. playing in the finals). And, above all, we lose faith in a well considered strategy far too easily (and, invariably, at the worst possible time).

If you haven’t seen the movie, we recommend it. We expect you’ll identify with some of the behavioural biases and see the parallels with applying a well researched plan and process for managing your wealth.