Is a company tax reduction a second best solution?

The Government has proposed to reduce the large company tax rate from its current 30% to 25% by 2026-27. It argues that the reduction is necessary to keep Australia’s company tax rate internationally competitive and will create “jobs and growth”, ultimately leading to wages growth.

It’s been a hard sell, with those opposing the move citing, among other things, the budgetary cost and a lack of confidence in the reliability of so-called “trickle down” benefits to Australian workers.

We don’t propose to enter into the argument as to whether a drop in the company tax rate is a good or bad thing for the Australian economy. However, as a generalisation, we don’t think a tax on companies is a particularly efficient tax, given the scope for avoidance and that shareholders ultimately bear the tax burden. Most likely, it would be more effective to tax shareholders directly.

This article examines some aspects of what a company tax reduction may mean for the returns for investors in company shares. These returns come in two forms – either as dividends and/or capital gains. We use some extreme examples to highlight some of the considerations.

How a company tax reduction may affect investors’ returns

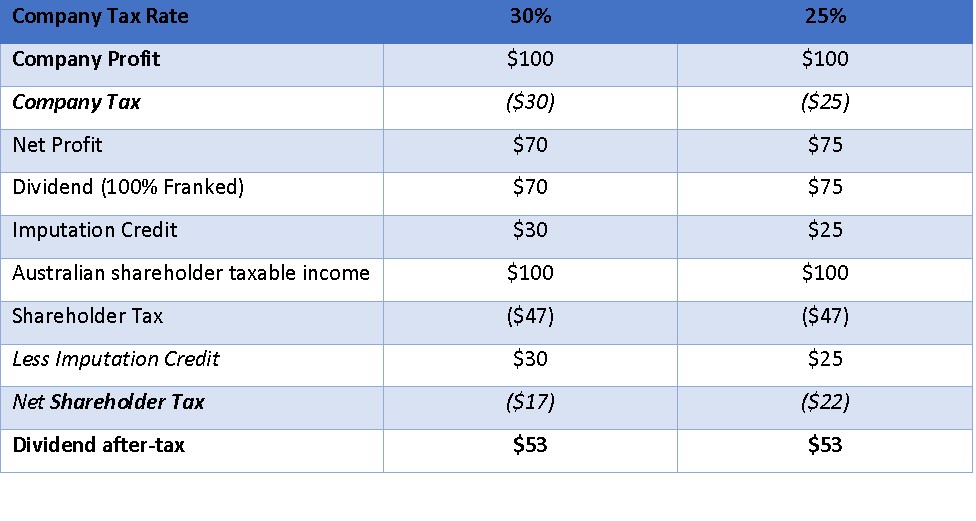

For simplicity, we initially look at the effect on shareholders of a company that pays out all of its profits as dividends and is 100% owned by Australians. We assume our shareholder pays tax at the top marginal tax rate (i.e. 47%, including Medicare levy). The table below shows how a $100 of this company’s profits and its shareholders are taxed under the Australian dividend imputation system, at both a 30% and a 25% company tax rate:

The Australian investor ends up with the same after-tax dividend, regardless of the company tax rate. The total tax payment of $47 remains unchanged but its distribution between the company and its shareholder changes.

Similarly, if we assume our shareholder has a 0% tax rate (e.g. a pension fund), the after-tax impact is no different. The tax rate reduction results in an after-tax dividend of $100, regardless of the company tax rate.

Given our assumption of a 100% payout of profits, there is no Government budgetary impact due to the reduction in the company tax rate – lower company tax receipts are exactly matched by higher personal income tax receipts. Also, because the company does not retain any of its increased after-tax profits, it’s hard to see how a change in the company tax rate would change share valuations.

So, in this admittedly unrealistic scenario, a reduction in the company tax rate is unlikely to have any impact on the total returns of Australian investors. But what happens when we change the assumptions, allowing for foreign investors and less than 100% dividend payout ratios.

Many foreign investors are unable to fully utilise Australian imputation or franking credits, in their respective tax jurisdictions. For those foreign investors who can’t use the credits, in the example above, the reduction in the company tax rate from 30% to 25% provides them with a windfall $5 increase in cash dividends for every $100 of company profits.

A higher cash dividend increases the return to foreign investors and, assuming nothing else changes, would be expected to result in an increase in the share price. The beneficiaries of the higher dividend will be foreign investors, while both foreign and Australian investors will benefit from the higher share price. The loser will be the Australian Government, as it will not receive the extra $5 in tax that the individual Australian investor pays in the example above.

The next issue to consider is the expected impact on returns when the company doesn’t pay out all its profits as dividends. Without any change in its (less than 100%) dividend payout ratio, a drop in the company tax rate will mean that the company retains more cash. For the example above, in the extreme case if the payout ratio is zero, the 5% reduction in the company tax rate will lead to the company retaining a further $5 for each $100 of profit.

Financial economics suggests that the value of a company is determined by the sum of its expected future after-tax cash flows discounted by an appropriate cost of capital (i.e. required investor return). On the face of it, a drop in the company tax rate would translate to an expectation of higher future after-tax cash flow and, therefore, an increase in value. But how much will depend on:

- The impact the lower company tax rate has on the cost of capital (e.g. the cost of capital could be expected to rise for a company with a high level of debt, as the after-tax cost of debt rises when the company tax rate falls); and

- the share market’s assessment of management’s ability to effectively use the additional funds.

Another potential implication of a company tax reduction is for shareholders to increasingly prefer that companies reduce dividend payout ratios (i.e. increase earnings retention). The rationale for this is clearest if a zero company tax rate is considered. In this case, a tax paying Australian shareholder is potentially better off not receiving regular dividends, leaving the funds in the company’s zero tax environment. Provided the company manages the increased funds responsibly, the investor would ultimately realise their return solely through capital gains and at a time of their choosing. Not only is tax deferral achieved, but capital gains currently receive valuable tax concessions.

In isolation, we expect a company tax reduction will increase shareholder returns

In summary, our analysis suggests the following potential implications for investors resulting from a reduction in the company tax rate:

- foreign investors are potentially the largest gainers, from higher cash dividends and, most likely, higher share prices;

- Australian investors’ after-tax dividends would be unchanged, but they would most likely benefit from higher share prices; and

- Personal tax considerations would increase investors’ preference for lower dividend payouts/higher earnings retention.

These conclusions are based on nothing else changing in share markets. Of course, the reality is that our expectations are likely to be swamped by unrelated, inevitable market gyrations, if and when the proposed tax changes are legislated.