What is index investing?

Many investors shy away from index investing because they deem it to be too naïve for their investment purposes. There’s definitely a higher seduction factor associated with a bottom up, active investment approach. Yet the recent trend has clearly been towards index style investing (due largely to the dissatisfaction with actively managed investment alternatives).

An index is a statistical measure for determining the performance of a portfolio of constituent investments. Charles Dow created the first (“Dow Jones”) index back in 1896 to act as a proxy for the performance of the US stock market as a whole.

You cannot invest directly in an index. You must rely on a manager who seeks to replicate the performance of an index – or try and do it yourself, which is a tough ask given that scale and costs matter. Index managers use a variety of techniques, from directly holding all of the constituents to a combination of direct holdings and the use of futures and options contracts.

Investors expect to earn the return of the index less the cost associated with managing the underlying portfolio. Accordingly, cost is a key decision driver and index managers are continually seeking better and cheaper ways to replicate an index’s performance.

An index is nothing more than a weighted list of securities – anybody can create one. There are different types of indices including market capitalisation (or “market cap”) weighted, price weighted and fundamental indices.

Historically, index portfolios have most commonly been market cap weighted. The S&P/ASX All Ordinaries Index is an example. It measures the performance of the top 500 listed companies on the Australian Stock Exchange and weights each share according to its market value. It reflects 98% of the collective asset weighted capital invested in Australian listed shares.

A fundamental index on the other hand, weights its constituents according to non-market cap criteria, such as dividend yields, revenue, book value, etc. The S&P/ASX Dividend Opportunities Index that measures the performance of high yielding shares is an example. It ranks all shares according to dividend yield and includes the top 50, weighting them according to their relative yields (rather than by market cap).

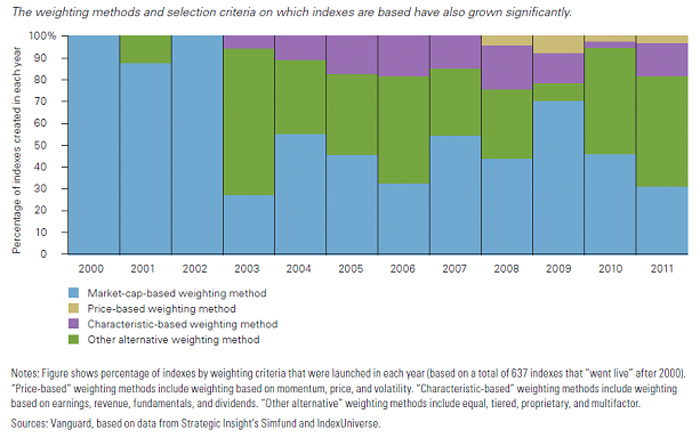

Recently, there has been significant growth in the number of indices. These are often created for the sole purpose of benchmarking an investment strategy. The chart below shows the percentages of indices, by weighting method, launched each year in the US since 2000.

Equity Index Creation by different weighting methods

The decline in use of market cap weighted indices reflects the criticism that they produce a negative performance drag. Because they systematically overweight companies with large capitalisation and those whose share price has risen faster than the index as a whole, it’s suggested that they underperform alternatively weighted indices (portfolios).

Does market cap weighted indexing result in underperformance?

We make the following observations:

1) The cheapest way of gaining exposure to an asset class is via a broad based market cap index fund. It offers exposure to all risk factors affecting the asset class. Investing via a fundamental index fund (for example) is an active bet on a particular factor (e.g. dividend yield) and will expose you to different risk and return characteristics;

2) The criticism of market cap weighted indices implies that it is easy to identify an alternative weighting structure that would outperform. In fact, the critics claim that any structure other than a market cap structure would outperform [1]. Jeffrey Graham [2] recently tested if market cap weighted indices exhibited a performance drag relative to a purely random-weighted scheme. He found no evidence of any such drag over the period from 1960 to 2009. The difference between the two approaches was statistically insignificant at 0.07% a year.

Unfortunately, this underperformance criticism has led to the development of numerous alternatively weighted indices that are often founded more on “data snooping” than on any sound investment principles;

3) Market cap weighted indices are far easier to replicate. The fact that the constituents’ weightings move in line with daily price movements means there is no need for continual re-balancing. A portfolio that tracks a fundamental index on the other hand requires continual re-balancing, meaning higher transaction costs. It also adds significantly to the complexity of the management process, which means it’s more costly to deliver (reducing the return for the investor); and

4) Tax consequences of managing a portfolio that requires more transacting can add a fairly material performance drag. Two portfolios with identical pre-tax performance will offer different after tax returns depending on the turnover of the portfolio. Turnover affects the timing of capital gains tax. A 10% portfolio turnover rate can deliver up to 16% more capital (after tax) than a portfolio with a 75% turnover rate (over a 30 year period) [3]. That’s quite a significant benefit that arises purely from transacting less.

Index investing – tougher to beat than it seems

Index investing offers many advantages for managing an individual’s wealth. It focuses on a top down investment methodology offering high diversification, transparency and a cost effective, process driven investment approach. It means portfolio construction techniques can be applied effectively without being high jacked by unsubstantiated (bottom up) active investment decisions.

Investment trends have seen an increasing use of an index based approach – the rise in Exchange Traded Fund offerings is a notable example. But there is also a trend towards a more active approach in this field, with an increasing number of indices and index based investment offerings.

This is partly driven by the belief that market cap weighted indices are a naïve way to invest. In our view, there’s more naivety with the use of many of these active index based approaches – rigorous research confirms it’s much tougher than it seems to beat a traditional indexing approach.

[1] As postulated by Hsu, J, 2006 in Cap-weighted portfolios are sub-optimal portfolios, Journal of investment Management and countered by Perold, A, 2007 in Fundamentally flawed Indexing, Financial Analysis Journal. [2] Jeffrey Graham, Journal of Investment Management, Fourth Quarter 2011. [3] Calculated based on two portfolios each earning a pre-tax return of 3.5% p.a. (income) and 5.4% p.a. (capital growth). The Calculations assume portfolio turnover rates of 10% and 75% and the total portfolio sale at year 30. The after tax outcomes were calculated for a tax payer with a marginal rate of 46.5% over the 30 year period.

1 Comment. Leave new

Useful. I agree.