High dividend paying shares appeal to many investors

High dividend paying shares appeal to many investors

It’s often suggested by various investment “experts” that the first requirement for a share investment is income return and then growth of capital. This implies that income return is a key driver of investment performance. Perhaps it explains why so many investors are so focused on income yield when choosing a share investment.

While we don’t know conclusively why investors have a preference for dividends over capital growth, some of the reasons we’ve heard include:

- I want to be able to preserve my capital;

- higher income return means I can retain my capital exposure and don’t have to sell anything;

- high yield shares are safer;

- I want to maximise my franking credits;

- shares prices can fall but at least I can rely on the dividend income; and, more recently,

- it’s a low growth world, so yield is more important.

Despite these preferences, we think it’s both simplistic and unnecessarily risky to build a share investment strategy based purely on income (dividend) yield. Ultimately, there’s a diversification cost from narrowing your investment opportunity set. Recent research sheds some light on the extent of this narrowing and other matters regarding dividend paying and non-dividend paying shares.

The facts about dividend paying shares

A recent research paper [1.] compared dividend paying and non-dividend paying shares over time to reveal some key aspects. The analysis focused on the shares from 23 developed markets over the 22 year period, from January 1991 to December 2012. It found the following:

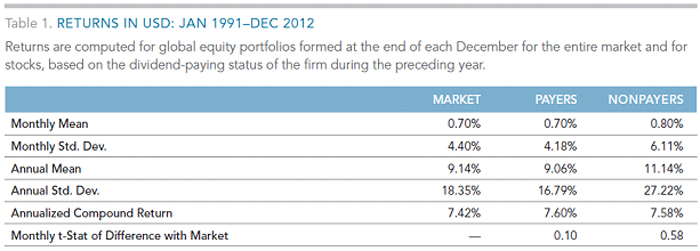

1) As shown in the table below, there was no material difference between the annualised compound return of dividend paying and non-dividend paying shares.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

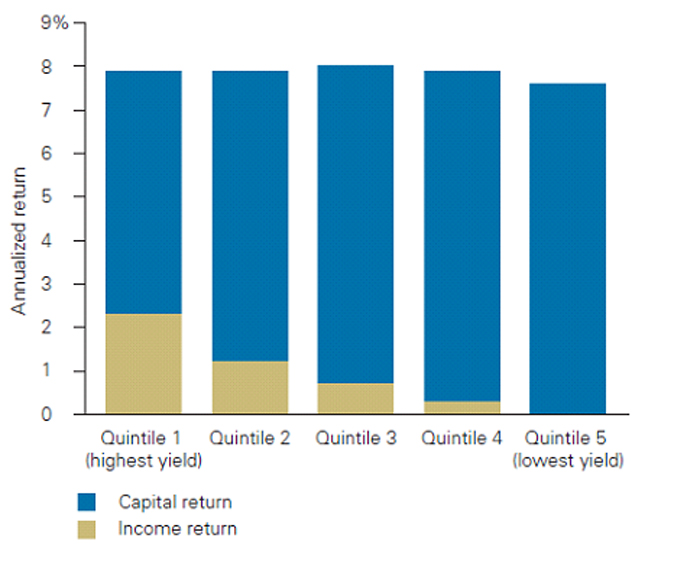

This was confirmed by a Vanguard study [2.] that also revealed no material difference between the average (income + capital) return of high yielding versus low yielding shares over a 20 year period (as shown in the chart below, that is copied from the study).

2) A global share portfolio constructed to provide a high dividend yield would have become more concentrated over time.

In order to capture 50% of the global dividend payout in 2012, you would have invested in 31% fewer firms than you would have in 1991. In fact, in 2012 you would only have had to have exposure to 2.4% of all global firms.

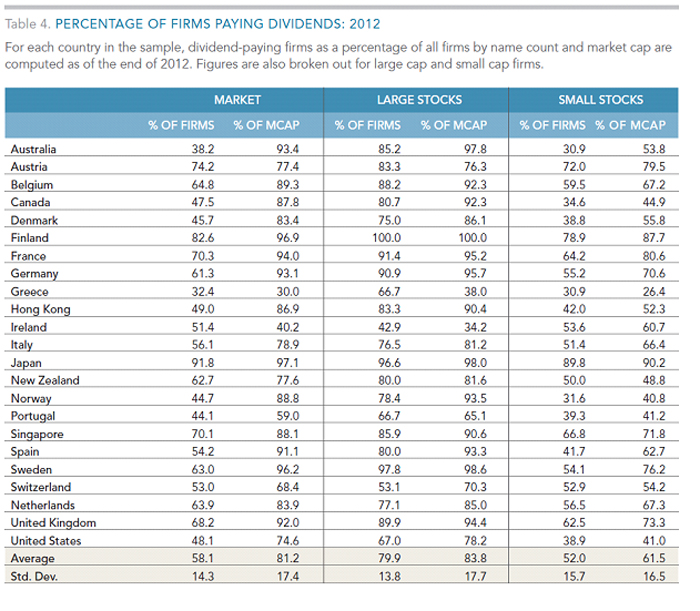

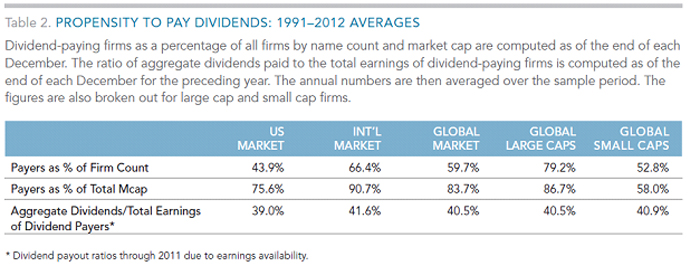

3) Larger firms are more likely to pay dividends than smaller firms, as revealed in the following table. This means a high yield strategy (unwittingly) forgoes the higher expected returns associated with investing in smaller companies.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

4) Globally, the weighted average book-to-market ratios of payers, nonpayers and the overall market were similar in 2012 (and over the 22 year period). This indicates no value bias, and hence no higher expected return (with associated higher risk), is introduced by adopting a high yield approach.

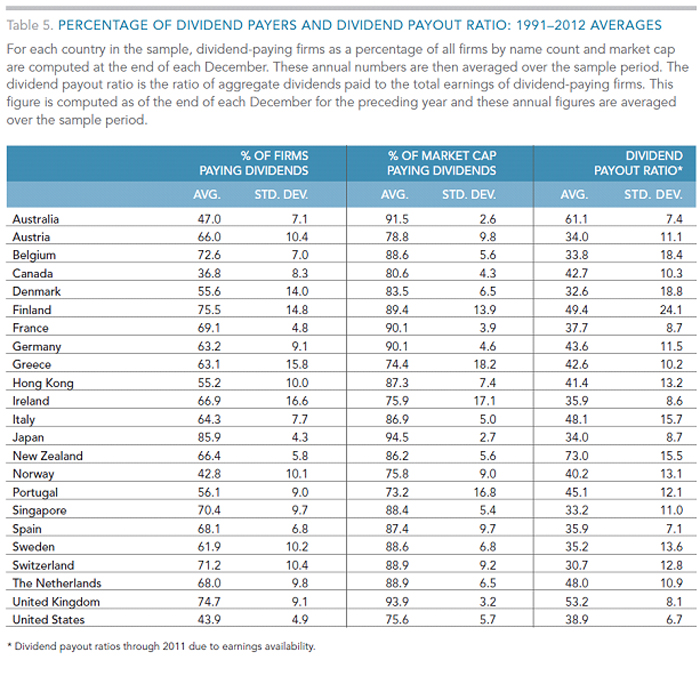

5) As revealed in the table below, there are cross-country variations in the proportions of firms paying dividends. For example, 92% of Japanese shares paid dividends in 2012 compared with only 38% of Australian shares. However, 85% of Australian large companies paid dividends, and they represented around 75% of the capitalisation of the Australian share market. A high yield strategy in Australia therefore would have resulted in a concentrated exposure to a small number of large company shares.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

And as shown below, when it comes to the payout ratio, Australian companies tend to return a lot to their shareholders, with an average payout ratio of 61% (second only to New Zealand at 73%).

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

Companies that offer regular and increasing dividends have a place in investment portfolios, but purchasing on this basis alone may be flawed decision making. Distributing most of earnings as dividends suggests that company management believes that the best use of the capital is to return it to shareholders, rather than reinvest it. This may say something about management’s view of the future growth prospects for their company.

It also appears some companies pursue attractive dividend policies in order to enhance their ability to raise capital. Metcash, for example, had a grossed up yield of over 11% last year. It had been paying out 80% of its earnings over previous years but recently went to the share market to raise $375 million of new capital. Seems like they’re raising funds to simply hand back to shareholders, the logic of which escapes us. In addition, some companies (e.g. Telstra) borrow money to maintain their dividend policy. Such practices serve to illustrate the issues associated with dividend yield as a reliable indicator of future performance.

Capturing the Equity Risk Premium

Buying a portfolio of high yield shares may ease your concerns about re-entering the share market, but it’s a riskier strategy than many appreciate. The costs with this approach, most notably the loss of diversification benefits, result in a sub-optimal investment exposure.

The aim of investing in shares is to capture the equity risk premium (i.e. the return for taking on equity risk). This should be approached using a methodical strategy that considers all the risk elements within the equity universe. Simply buying a portfolio of high yielding shares is unlikely to meet this requirement.

[1.] Stanley Black, March 2013, Global Dividend-Paying Stocks: A Recent History, Dimensional Fund Advisors.

[2.] Jaconetti, Kinniry & Philips, November 2012, Total-return investing: An enduring solution for low yields, The Vanguard Group.

1 Comment. Leave new

This article notes the trend for companies to pay dividends that outstrip earnings – a sign that companies prefer to repay shareholders than look for investment opportunities. Is it driven by a desire to attract shareholders or a lack of viable investment opportunities? http://m.theage.com.au/money/investing/caution-starting-to-pay-dividends-20130903-2t1jk.html