Good financial health not measured purely by wealth

When we started Wealth Foundations in 2007, we embraced 20 principles of successful wealth management. These continue to underpin our approach to personal financial planning.

Principle 17 states that: “Money is a means to an end, not an end in itself”. Our original rationale for this principle was as explained below:

“Research indicates that a pursuit of wealth and its trappings for their own sake is unlikely to result in life satisfaction. Also, it is important to realise that maximising wealth may be a poor proxy for maximising life satisfaction.

Therefore, we believe that effective wealth management requires you to first examine and articulate what is important to you in life (i.e. your lifestyle objectives) and then consider what, if anything, may need to change financially for those objectives to be achieved. To blindly pursue increased wealth without first asking “what for?” is really putting the cart before the horse.”

In summary, we didn’t, and still don’t, believe that the state of your financial health is measured simply by the number of dollars you have. Nor does an increase in the number of those dollars necessarily mean that your financial health has improved. It may simply serve to feed a potentially unhealthy addiction.

A recent paper by Morningstar Behaviour Economist, Sarah Newcomb, titled “When More is Less; Rethinking Financial Health”, provides some research backed insights into the nature of “Financial Wellness”. Focus groups conducted with financial advisers for her study revealed numerous examples of apparent financial ill-health that we have also observed:

“There are the clients who fear not having enough, despite every indication to the contrary. There are those so fearful of making a wrong choice that they refuse to make any, leaving their wealth to slowly erode in cash accounts. Other clients, in contrast, spend too freely, choosing blissful ignorance about the damage to their bottom line.”

Newcomb’s observation is that financial wellness needs to incorporate both economic and emotional aspects of well-being. She suggests that, regardless of wealth, you can’t be considered financially healthy if your financial situation is an ongoing source of emotional stress.

Given this viewpoint, her paper examines the application of two principles of psychology to improve financial health – the first aimed at enhancing economic stability with the second directed at emotional well-being. These are examined in the remainder of the article.

Using psychology to improve financial health

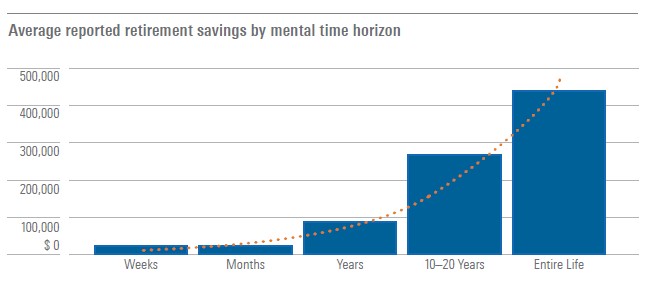

With regard to improving economic stability, Morningstar research indicates that people who think further into the future (i.e. have a longer mental time horizon) tend to save more frequently and build larger retirement balances, as illustrated in the chart below:

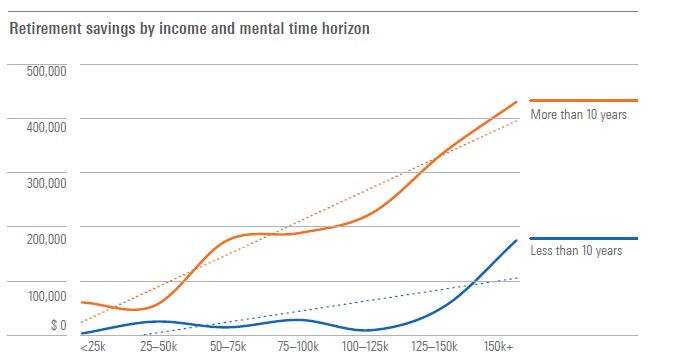

This finding holds regardless of other potentially influencing factors such as age, income, gender and education. For example, the following chart from the Morningstar research reveals that those who thought further ahead (i.e. more than 10 years) on incomes of around $50-75,000 saved as much for retirement as those with shorter time horizons (i.e. less than 10 years) on incomes categorised as $150,000+.

Therefore, Newcomb concludes that to improve people’s economic stability an important prerequisite is for them to improve their ability to think longer term. One technique to achieve this is for them to regularly imagine how they would like their life to be one year hence and then extend the visioning out to 5, 10 and 20 years.

They should attempt to describe their ideal financial futures in as much detail as possible, rather than use vague descriptions such as “I want to be financially secure” or “I want to have peace of mind”. Corroborating research shows that the more people are able to identify with their future selves, the more emphasis they place now on securing their envisioned future, and not only from a financial perspective.

With regard to improving emotional well-being, Newcomb’s research indicates that people who feel empowered in their financial lives experience more joy, peace, satisfaction and pride with their financial circumstances than those who don’t. From a financial adviser’s perspective, Newcomb suggests that client empowerment is enhanced by ensuring clients are fully involved in decision making and given regular reminders of the progress they are making.

“Money is a great servant but a bad master” – Francis Bacon

Newcomb notes that money is the number one source of stress in US households, regardless of economic climate, according to The American Psychological Association. We would be surprised if the Australian experience is different.

But “more money” is not necessarily the antidote. In some cases (e.g. pursuing more wealth for its own sake), it may only reinforce an already poor emotional relationship with money.

Newcomb argues that sound financial health is characterised by high levels of economic stability and emotional well-being (around money). We regard this as consistent with our “Money is a means to an end, not an end in itself” principle, that suggests it is your concept of what is “a good life” that should drive your wealth needs, rather than any emotional issues you may have with money.