Our feelings aren’t reliable indicators of future investment returns

Our feelings aren’t reliable indicators of future investment returns

If you let it, investing can be an emotional roller coaster. But while in many walks of life how we feel may be an important input to decision making, letting short term emotions substitute for a soundly constructed long term investment strategy is generally not a good idea.

For example, the emotions of fear and greed, allowed to run unchecked, can drive behaviours that are deleterious to our financial health. Evidence shows we often rush to sell when share (and property) markets are at their gloomiest (with prices relatively low) and fall over ourselves to buy when asset prices have risen and are relatively high. Consistently selling low and buying high is a sure fire way to go broke.

Most of us are averse to investment risk, meaning we need increasing dollops of expected return to take more of it. This suggests that there should be increased reluctance to purchase shares and property as prices rise, because expected returns are falling.

But this is not what generally happens. It seems that our perception of risk changes, depending on market circumstances. After a strong and sustained run up in share or property markets, we are inclined to feel these markets are less risky, despite no actual change in risk. Usually unwittingly, we demonstrate that we are comfortable with the lower expected returns that are a corollary of higher prices, and continue to buy at a time when we should probably be reducing our risk exposure.

For many, the volatility of share markets is very unsettling. We crave increased certainty of return but also want and, often, need higher returns. We want to believe that one of the cast iron rules of finance, that risk and return are related, can be suspended.

This makes us suckers for complex structured products that, apparently, have little downside risk but with upside potential. The only certain long term beneficiaries of such, usually costly, products are the financial engineers that create them. It also makes us suckers for anyone who claims they know what the future holds.

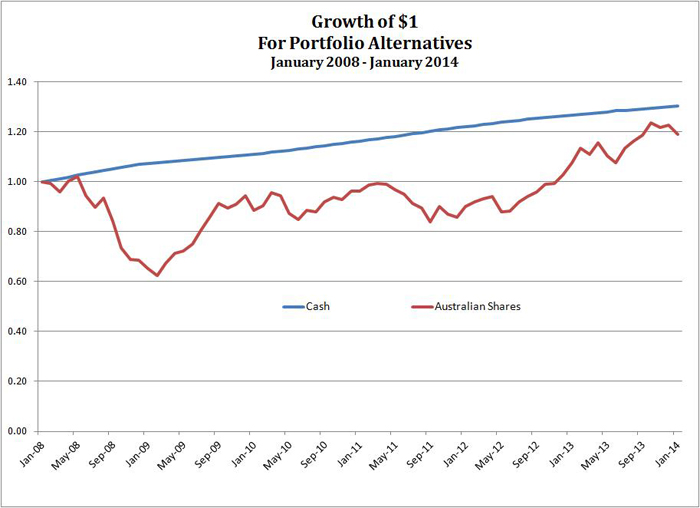

The past six years have been a very turbulent period for investment markets. From the gloomy depths of early 2009 to the strong and, for some, confounding, performance of domestic and, particularly, international share markets over the past 12 months. Below, we revisit this period to reveal that how we felt at particular times could have led us to make exactly the wrong investment decisions.

The emotional investment roller coaster of 2008-2014

The chart below shows the growth of a $1 invested in cash and Australian shares for the period from January 2008 to January 2014:

With the benefit of hindsight, a very effective strategy (the “hindsight” strategy) over this period would have been to:

- enter the GFC, in early 2008, 100% invested in cash;

- move 100% to shares in about March 2009;

- move back to cash in about March 2011; and

- move back to shares in May 2012.

In the chart below, we show what an even better strategy – represented by a “perfect foresight” portfolio – could have achieved i.e. on a monthly basis, switching between cash and shares depending on which proved to be the higher performer the following month. If only!

But ignoring for the moment the difficulty in picking the time to enter or exit markets, consider the feelings experienced at the time of implementing each step of the “hindsight” strategy.

Over the three years prior to December 2007, the Australian share market rose 77%. To be fully invested in cash in early 2008 after such exhilarating share market performance required either luck or a strongly contrarian nature – the rare ability to stand in defiance of the herd.

However, given the fear that gripped the world around February 2009 and following an almost 40% decline in the Australian share market, a decision to move from cash to 100% shares at that time would have taken nerves of steel. For most, their feelings were telling them to sell shares, not buy more.

By March 2011, many were starting to think the worst of the GFC was behind us and the share market, after an almost 60% recovery, was starting to look a safer, lower risk bet. There was no way most investors’ emotions would be telling them that it was the time to switch back to cash.

Yet by December 2011, doom and gloom again dominated. I remember a long standing client being advised by family members over the 2011 Christmas period that she should sell down all her growth assets, as the world economy was an intractable mess. Fortunately, she resisted her family’s feelings and has benefited from a subsequent 39% rise in the Australian share market.

Your emotions are more likely to drive poor investment decisions

Most of us would accept the impossibility of achieving investment returns implied by the “Perfect Foresight Portfolio” charted above but, perhaps, expect that something approaching it should be the goal. However, the reality is that if you believe good investment practice requires you to:

- make mostly correct decisions about the future; and

- let your feelings influence investment decisions

then you must accept the possibility that your investment results could also look more like the “Imperfect Foresight Portfolio” shown in the graph below i.e. getting every call wrong.

Something approaching this result would ruin most people’s lifestyle plans. Unfortunately, for those who let their emotions rule their investment decisions, easily avoidable financial disasters occur too frequently.

Is there a way to have a satisfactory investment experience that doesn’t depend on how you feel and the quality of your forecasts? We believe there is and some alternatives are discussed in our next article.