Borrowing to invest has appeal to some high income professionals

Borrowing to invest has appeal to some high income professionals

The Global Financial Crisis clearly revealed the dangers of attempting to accelerate wealth accumulation by borrowing to invest. Many were left owing considerably more to their lenders than their investment assets were worth.

However, for many high income earning professionals in their late 40’s-early 50’s, borrowing to invest (for shares and property) continues to appeal. The combination of:

- the desire to maintain a good quality lifestyle, while simultaneously building wealth for a retirement that is looming larger;

- strong debt servicing capability; and

- tax deductibility of interest

make gearing strategies (i.e. borrowing to invest) a relatively easy sell to this group. While the risks are usually touched on, income earning ability is emphasised as an offsetting factor that makes those risks manageable.

The alternative of reducing spending and investing the increased savings to accumulate investment wealth is often not viewed favourably. Particularly when gearing offers the opportunity to “have your cake and eat it” and, simultaneously, reduce a high tax burden. Lifestyle reductions impact now, while increased downside risk is not immediately tangible and may never reveal itself.

This article examines the real dangers of relying on a borrowing to invest strategy as a solution to an unwillingness to save problem for high income professionals.

Borrowing to invest requires a high risk tolerance

Consider John Smith, a barrister, who is aged 45 and has an annual household pre-tax income of $800,000. He expects his income to increase at 1% p.a. above inflation to his proposed retirement at age 65.

Currently, he is spending $320,000 p.a. (i.e. 40% of pre-tax income), that he also projects to grow at 1% p.a. above inflation to age 65. Savings of about $94,000 are implied for this year.

In retirement, he would like to be able to spend about $270,000 p.a. in today’s dollars. He owns his home, but has not accumulated any investment wealth.

John goes to a financial planner to discuss the reasonableness of his expectations. Using the “Rule of 25”, the adviser suggests he will need to accumulate around $6.8 million in today’s dollars to give him a high chance of meeting his retirement spending aspirations.

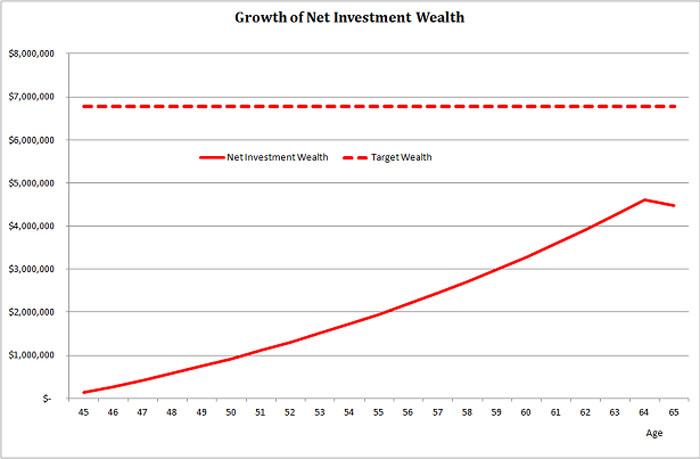

Applying some reasonable growth investment assumptions [1.], the adviser shows that John’s savings will accumulate to about $4.5 million by his age 65, as revealed in the chart below: well short of the target of $6.8 million.

The solutions offered are:

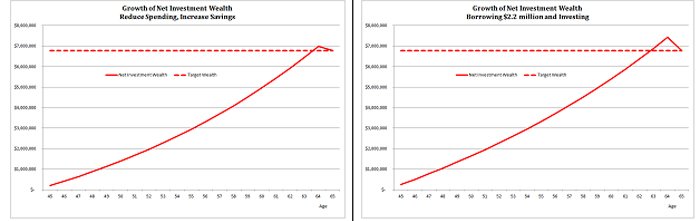

- John’s family can increase savings to invest by reducing initial expenditure to about 31.5% of income or to $250,000 p.a., compared with the current $320,000 p.a.; or

- Maintain expenditure and borrow a little over $2.2 million to invest in growth assets.

The charts above are provided to show that target wealth is achievable under both scenarios. With the borrow to invest option, John can easily service the debt and there is no immediate lifestyle pain. It may be convenient for both adviser and client not to focus too heavily on the significantly different risk characteristics of the two scenarios.

But the simple analysis described above fails to take account of the volatility of investment returns: the possibility that although the assumed projections may even prove correct over the long term, over the short term almost anything is possible.

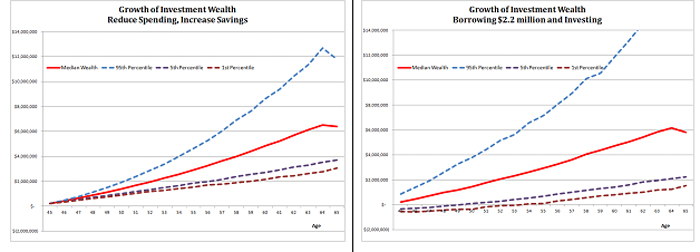

To get some appreciation of the impact on wealth possibilities of volatile investment returns, we use a technique called Monte Carlo analysis. It allows us to simulate thousands of potential wealth paths, based on generating series of random investment returns using historical investment returns and volatilities.

The charts below show the results of simulating 2,000 wealth paths for the two scenarios i.e.:

- Reduce spending to increase savings for investment; and

- Borrow $2.2 million and invest, with no change in spending.

They use the same average investment returns as those in the analysis above and incorporate volatility estimates [2.] roughly consistent with historical data.

Focusing on potentially poor return outcomes (i.e. the 5th and 1st percentiles), investment wealth is never negative for the reduced spending scenario. However, in the borrowing to invest scenario investment wealth is negative (i.e. the value of investments is less than borrowings) until John turns 49 for 5% of the simulations and until he turns 54 for 1% of the simulations.

The question we would ask is does John have the risk tolerance to “stomach” being underwater for an extended period in adverse markets. Or will he abandon the strategy at the first sign of trouble, to replace it with “who knows what”?

Also, for more than 50% of the simulations (represented by the median – the red line), the reduced spending scenario results in higher age 65 wealth than for the borrow to invest scenario. It is only when returns prove to be better than historical averages that the borrow to invest strategy dominates. In these situations, more retirement wealth than actually required is generated.

The risks of “borrowing to invest” need to be given due consideration

Despite often appearing to be the least painful option to achieve wealth accumulation objectives, borrowing to invest can result in a lot of financial and psychological pain for high income professionals.

And, the strategy reduces flexibility. John better not change his mind about working, or not be able to work, at something like his current capacity for the next 20 years, with $2.2 million of borrowings to continually service and eventually repay.

We’re not suggesting borrowing to invest is never an appropriate strategy. It may be, particularly for those early in their careers. But the risks, even for high income professionals, are high and need to be carefully considered.

[1.] Key assumptions include:

- Inflation of 4% p.a.;

- Growth asset income of 3% p.a., 50% franked, and growth of 7% p.a.;

- Borrowing rate of 7% p.a.; and

- A marginal tax rate of 46.5%.

2 Comments. Leave new

[…] Follow this link: Borrowing to invest a risky solution to a savings problem : : Wealth … […]

Firstly, well done in examining these issues. The continued propensity for our industry to ignore even a basic examination of these issues is amazing given the GFC wakeup call.

One point I do think that is relevant is the use on Monte Carlo to examine these scenarios. The additional ‘what ifs’ imposed on a gearing strategy through Margin Lending make the assessment even more complex.

Given that Monte Carlo analysis has trouble with return sequencing (that is it assume random returns +/- a std deviation each year) it cant articulate very well the impact the real life market corrections often displayed (i.e multiple years of poor and large value falls). This suggests that the probability of our investor being underwater for extend periods of time is somewhat understated in this simulation.

Additionally, adding a premium of at least 2% on your interest rate assumption would be required for margin loan scenarios. This further reduces not only the size of potential out performance but also its probability of occurring.

Now the real probability data starts to emerge, being ‘yes’ you have the potential for larger returns than a non geared strategy, but the tradeoff is that you are more likely to fail in reaching both targets!

The other point is the dreaded margin call. In those underwater scenarios our investor is unlikely to have the luxury of just sitting tight and riding it out.

At a 50% LVR a 30% market fall would trigger a $300,000 margin call. at 60% LVR (quite common pre GFC) that margin call is $817,000!! (assuming the need to reduce the LVR from 71% to 65%).

Now our barrister is certainly ok on $800,000 pa by 99% of the populations standards. But even for him those kind of numbers could result in potential financial armageddon unless he has access to credit lines. At the very least he would be forced to sell down a considerable portion of those investments, a process likely to result in negative equity even with a swift market recovery. And after that he will find himself lucky to even reach his first ~$4m retirement target let alone the ~$6m goal.

I wonder how many such scenarios would have been easily avoided had clients been provided with analysis such as this…. Who knows, but we can be certain there would have been a whole lot less product sales for the adviser involved!