The real risk is running out of money

In turbulent and generally downbeat financial markets, like we have experienced since the end of 2007, there is natural tendency to become more cautious. To spend less, save more, pay-off debt and, particularly for those close to or in retirement, hold more investment wealth in defensive assets i.e. cash and fixed interest.

We may get a sense of comfort from knowing that the value of our investments cannot fall further and believe we have adopted a sensible, low risk investment strategy. And this is certainly true, if you think that investment risk is measured solely by the volatility of investment returns, pre inflation and tax.

But if the risk you are more concerned about is that you won’t be able to live the lifestyle you want or that your money might run out before you do, then high levels of defensiveness may be very risky.

Your lifestyle expectations and investment risk may not match

We have no idea of what the future will bring, so need to resort to the past to help illustrate the potential risk of letting your investment strategy be determined by an emotional response to volatile markets rather than by other more objective factors.

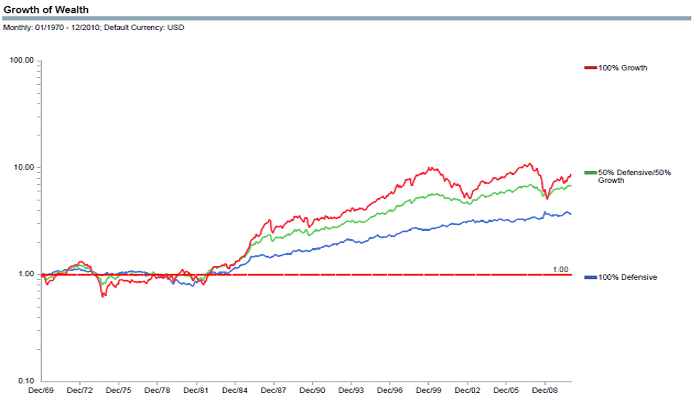

Below, we examine three portfolios, a 100% defensive portfolio, a balanced portfolio (i.e. 50% defensive/50% growth) and a 100% growth portfolio, using US data for the period December 1969 to December 2010:

Defensive Portfolio Allocation (%) | Balanced Portfolio Allocation (%) | Growth Portfolio Allocation (%) | |

| US Certificates of Deposits | 50 | 25 | 0 |

| US Long Term Government Bonds | 50 | 25 | 0 |

| Defensive Assets | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| Large US Shares (S&P 500) | 0 | 30 | 60 |

| Large International Shares (MSCI EAFE) | 0 | 20 | 40 |

| Growth Assets | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Average return (% p.a., after inflation) | 3.5 | 5.4 | 7.2 |

| Annualised return (% p.a., after inflation) | 3.2 | 4.8 | 5.4 |

| Volatility (% p.a.) | 7.3 | 10.5 | 18.7 |

Volatility of 7.3% for the defensive portfolio suggests that 68% of the annual returns varied between -3.8% and 10.8%. Note that the returns are after inflation. The comparable figures were -5.1% and 15.9% for the balanced portfolio and -11.5% and 25.9% for the growth portfolio.

The chart below, that is scaled on a log or proportional basis, shows the growth of a $1 for each portfolio over the period and reveals that:

- the growth portfolio achieved the highest accumulated value; but

- an investor would have needed to cope with extreme volatility to reap the rewards.

This history is useful in the sense that it shows that at least in the past investors have been rewarded for taking greater risk. But they needed to be patient and have nerves of steel, given the volatility of returns.

But even for a retiree with nerves of steel, the above analysis may not be very helpful. The reality is that the future is unlikely to look like the past and investment capital is not left untouched but is regularly rundown to meet living expenses.

However, if we are prepared to make the (admittedly heroic) assumption that future returns will come from the same distribution as those of the past (i.e. same expected (but not guaranteed) returns and volatilities), we can use a technique called Monte Carlo analysis to show for a typical retiree:

- a potential range of wealth outcomes; and

- the likelihood of running out of money

for various levels of desired future expenditure.

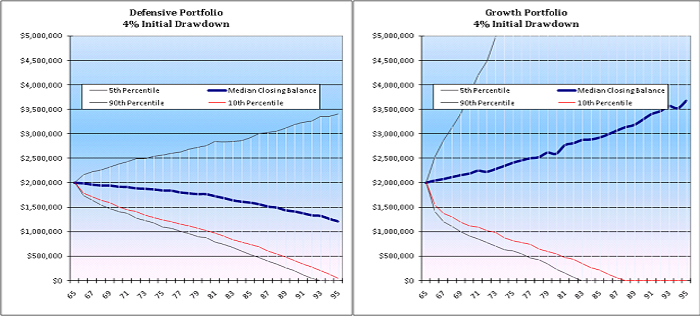

To illustrate, we assume a 65 year old retiree with an initial investment wealth of $2 million and a desire to spend $80,000 p.a. in today’s dollars (i.e. 4% drawdown of initial wealth) for the rest of his life. Using the expected returns and volatilities of the portfolios, we can simulate any number of potential wealth paths for each portfolio and the probability of running out of wealth at any particular future age.

The charts below show the range of wealth paths for the defensive and growth portfolios based on these assumptions and 1,000 simulations:

As is apparent, increased defensiveness narrows the range of possible wealth outcomes, at the expense of potentially building a significantly larger estate. For this scenario, the probability of consuming all wealth by age 95 is 8.8% for the defensive portfolio and 19.1% for the growth portfolio, suggesting maximum defensiveness is a virtue. But the probability of running out of wealth at age 95 for the balanced portfolio is an even lower 5.1%.

The table below shows the probability of running out of wealth at age 95 for the three portfolios for a range of desired expenditure (initial drawdown) levels:

Probability (Wealth)=0 at age 95

| Expenditure( Initial Drawdown %) | Defensive Portfolio | Balanced Portfolio | Growth Portfolio |

| $60,000 (3%) | 0.3% | 0.6% | 7.9% |

| $80,000 (4%) | 8.8% | 5.1% | 19.1% |

| $100,000 (5%) | 41.3% | 20.3% | 31.2% |

| $120,000 (6%) | 73.0% | 42.4% | 42.7% |

The analysis suggests that as lifestyle expectations rise (i.e. desired expenditure increases), the defensive portfolio becomes increasingly risky and the growth portfolio relatively less risky, as measured by the likelihood of running out of money.

Low investment risk dictates relatively modest lifestyle expectations

While the above discussion is based on a number of assumptions, there are some conclusions that we think hold up under a broad range of circumstances if the risk you are most concerned about is that of consuming all your wealth. These include:

- a highly defensive portfolio only makes sense only if you have modest lifestyle expectations relative to your investment wealth and the size of your estate is not a major issue;

- the higher your lifestyle expectations relative to your wealth, the more growth oriented your portfolio needs to be;

- your growth allocation should not exceed your tolerance for risk, to reduce the possibility that your emotions drive you to abandon a well formulated investment strategy when growth assets perform poorly; and

- the preferred way to adjust to prolonged market downturns is to reduce expenditure expectations, rather than to increase defensiveness.

And these conclusions are made before taking account of the relatively unfavourable tax treatment that applies to defensive assets compared with growth assets.