Reserve Bank Governor notes retirement has become more expensive

In a recent speech to the “Australian Financial Review” Banking and Wealth Summit, the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Glenn Stevens asked a very important question:

“How will an adequate flow of income be generated for the retirement community in the future, in a world in which long-term nominal returns on low-risk assets are so low?”

He further observed that:

“Just about everywhere in the world the price of buying a given annual flow of future income has gone up a lot. Those seeking to make that purchase now – that is, those on the brink of leaving the workforce – are in a much worse position than those who made it a decade ago. They have to accept a lot more risk to generate the expected flow of income they want.”

Stevens didn’t provide an answer to his question and we don’t pretend that we have it either. However, we consider there are some aspects of Stevens’ comments worth exploring further.

Falls in real interest rates and increased longevity raise the cost of retirement

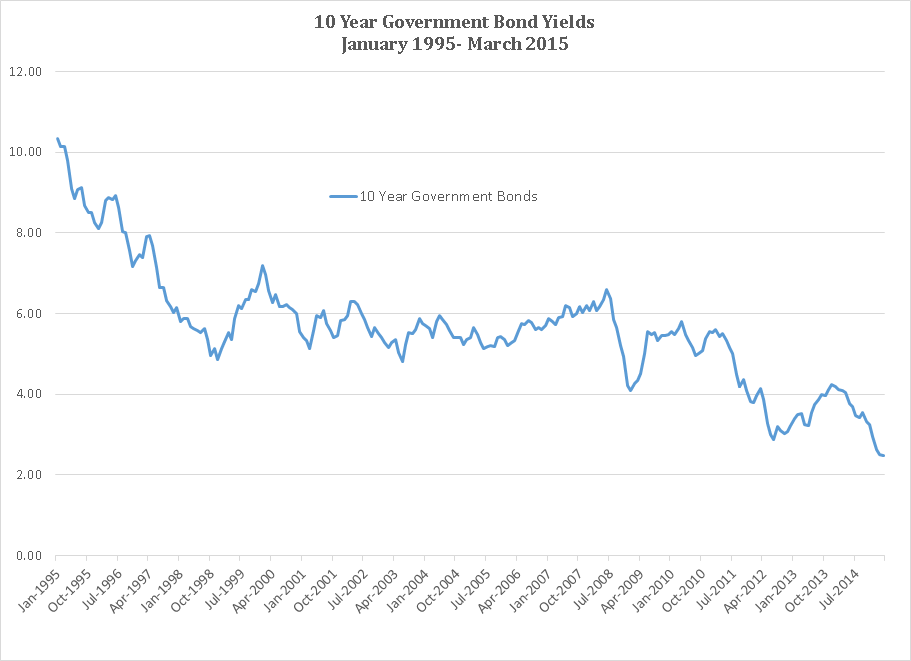

The chart below of 10 year government bond yields shows the steep decline that has occurred over the past 20 years.

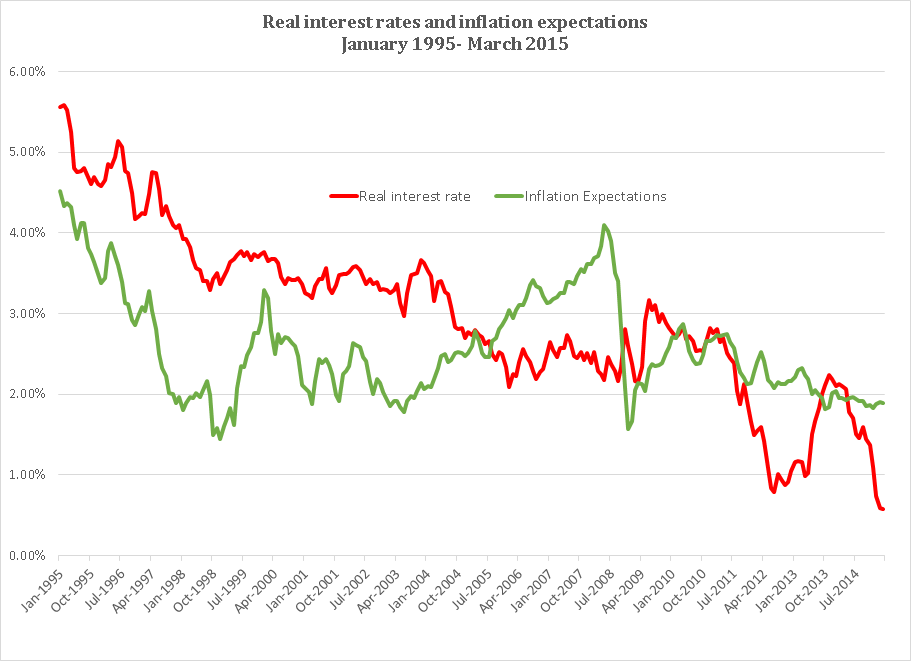

Nominal bond yields are composed of both an expectation of future inflation and a real interest rate, that provides an indication of future expectations for the economy (i.e. low real rates are a product of low confidence to invest and spend). The chart below attempts to isolate these components, calculating inflation expectations as the difference between the Government 10 year bond yield and the inflation indexed bond yield (i.e. a real interest rate):

It reveals that the fall in actual bond rates over the past decade has been primarily driven by the fall in real interest rates, rather than a fall in inflation expectations. It is this fall, that reflects pessimism regarding future prospects for the economy, rather than the fall in actual bond yields that has increased the cost of funding retirement.

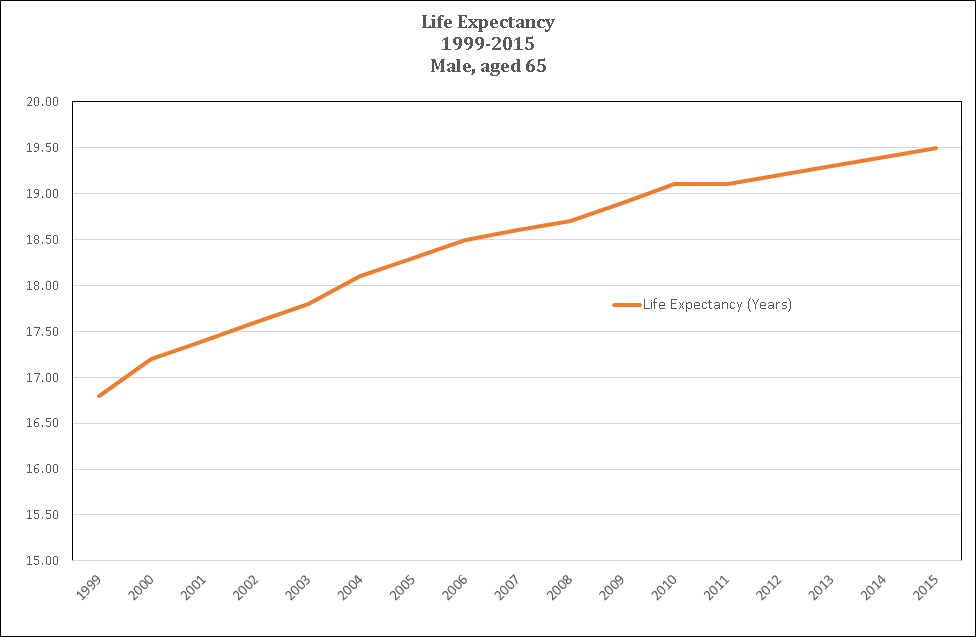

In addition, life expectancy continues to increase so people need to be able to financially support themselves for longer. The chart below shows how life expectancy, for a male aged 65, has increased since 1999.

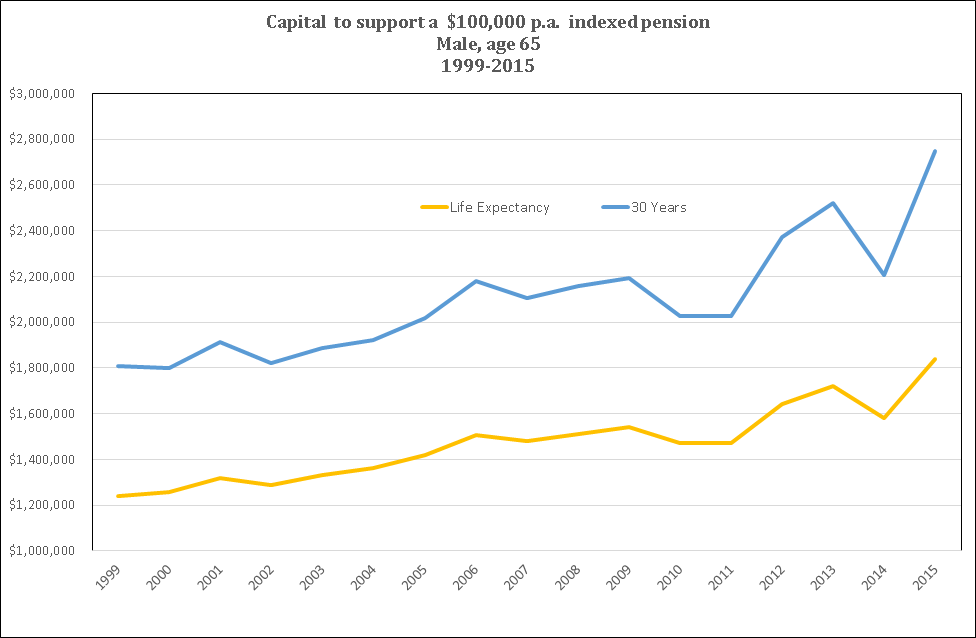

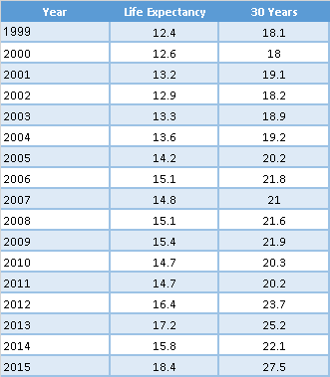

So what has been the impact of declining real yields and increased longevity on the cost of retirement? The chart below shows for each year from 1999-2015 the capital sum (“capital cost”) required to support a $100,000 p.a. CPI indexed pension for a 65 year old male both to his life expectancy and for 30 years, assuming the capital is invested at the relevant indexed bond rate:

Supporting the Reserve Bank Governor’s observations, the cost of the “life expectancy” pension has risen by a massive 48% since 1999 and 30% over the past 10 years. For those wishing to lock in 30 years of pension income, the cost has increased by 52% since 1999 and 36% since 2005.

It is interesting to note that the analysis also suggests that the capital cost of providing the current single age pension of $21,913 p.a. to a 65 year old male has risen from a minimum value of about $272,000 in 1999 to $403,000 now. On the same basis, the combined pension for a couple of $33,036 p.a. would now require more than $600,000 to support.

The actual capital costs are likely to be higher, as age pensions are linked to at least the CPI increase and may increase faster if other price indicators rise more quickly. Despite criticism regarding the adequacy of the age pension, we suspect most people would be surprised at its implied cost.

Another observation from the analysis is that the ratio of the capital cost to the annual pension income requirement is similar to our “Rule of 25” benchmark. As a rough rule of thumb, for financial independence we suggest clients should accumulate investment wealth of at least 25 times their desired annual spending.

The table below reveals the ratio of capital cost to pension income for the period 1999-2015 for both the life expectancy and 30 year pension:

For the 30 year pension, reduced real interest rates have resulted in the multiple of pension income rising from 18.1 in 1999 to 27.5 now.

More investment risk unlikely to be the answer

The Reserve Bank Governor suggests that low interest rates are forcing the current crop of retirees to take on higher risk investments in the hope of meeting their income requirements. It has simply become too expensive for most to purchase a genuinely low risk solution.

So they are looking for investments that history has suggested to them are at the lower end of the risk spectrum, such as bank shares and residential property. And often, borrowing to finance these investments. What could possibly go wrong?

The concern, of course, is that the step up the risk curve is being taken at a time of their lives when, if things do go wrong, there is little or no capacity to recover. They will be forced to accept a potentially much lower standard of living.

Although it may be unpalatable, our view is that such retirees should lower their expectations or, if possible, work longer rather than stray either purposely or unwittingly outside their investment risk comfort zone.