Comparatively, house prices may appear reasonable

Comparatively, house prices may appear reasonable

In a recent speech, titled “The Lucky Country”, the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Mr Glenn Stevens, argues that despite many pundits suggesting otherwise it is hard to provide a definitive answer to the question “Are dwelling prices too high?”

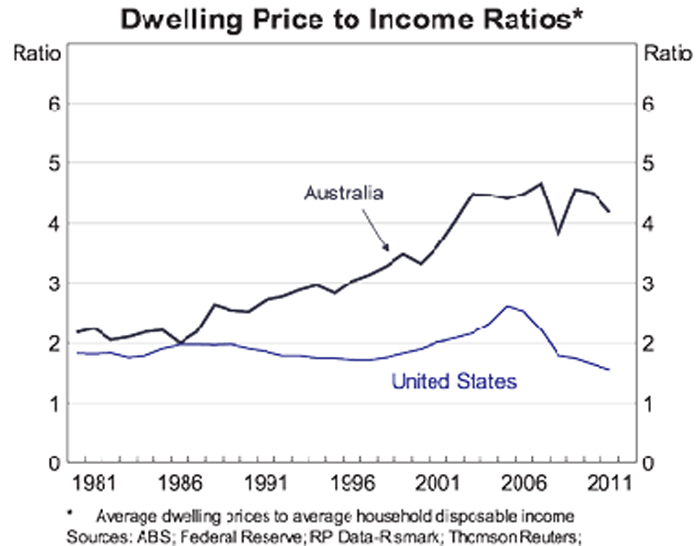

He draws on two charts to support his viewpoint. The first (shown below) reveals that both historically and compared to the United States our “Dwelling Price to Income” ratio is high, initially suggestive that housing prices are overvalued.

But, Stevens notes, “there is no particular basis to think that the price to income ratio 20 years ago was “correct”. He goes on to state that “arguments that appeal to historical averages for such ratios lose potency the longer the ratio stays high”. Perhaps, a ratio of 4-4 ½ may be the “new normal”.

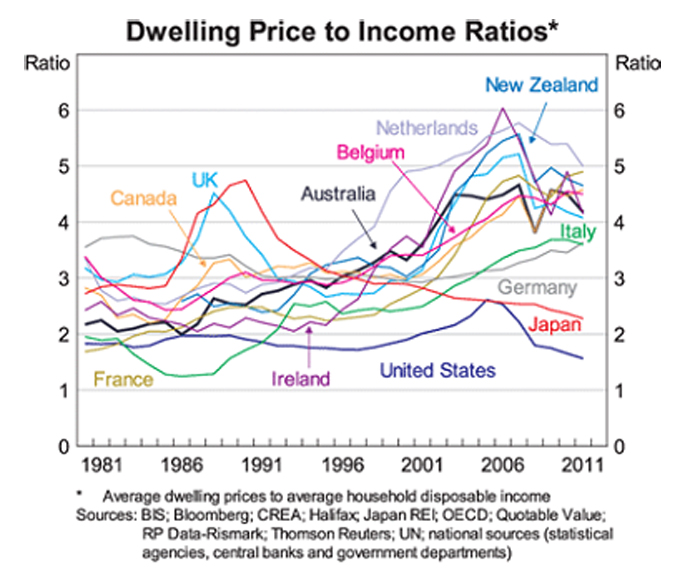

And, when compared with a number of other developed countries’ Dwelling Price to Income ratios (as shown in the following chart), he suggests that the United States rather than Australia “seems the outlier”.

While the Governor does not conclude that housing prices cannot fall, he suggests that “historical or international comparisons … do not constitute definitive evidence of an imminent slump.”

However, while we agree with this summation, we don’t think “Dwelling Price to Income” ratios of 4 – 4 ½ are sustainable over the long term, unless there are some radical changes in the way Australians think about our financial futures. They are unlikely to be the “new norm”. In a nutshell, at current “Dwelling Price to Income” ratios residential property is too large a percentage of our personal wealth and something will eventually have to give.

But a “Dwelling Price to Income” ratio of 4 ½ is too high

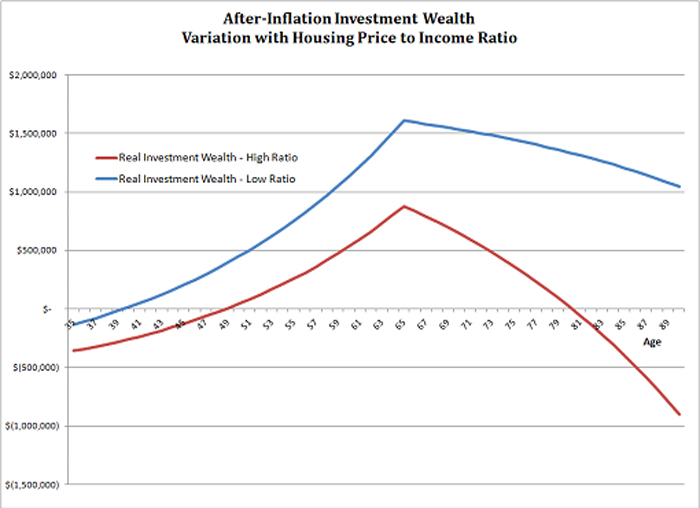

Some simple long term affordability analysis leads us to this view. Consider two households with the oldest adult in each household currently aged 35. Both households are exactly the same in terms of current household income, house deposit saved, expenditure, income growth and expected future expenditure. The only difference between them is the purchase price of their homes. The “Low Ratio” household purchases their residence at 2 ¼ times household income and the “High Ratio” household purchases theirs at 4 ½ times household income.

We assume an initial household income of $100,000 a year, but the conclusions do not vary significantly with income. Based on a $100,000 income, the “Low Ratio” residence costs $225,000 and the “High Ratio” residence $450,000. The “High Ratio” household needs to borrow 80% of the value from the bank, implying a deposit requirement of $90,000 and a loan of $360,000. The “Low Ratio” household only needs to borrow $135,000, given they also have a deposit of $90,000.

We then project each household’s investment wealth (excluding the value of their homes and net of borrowings) to a retirement age of 65 and then for the next 25 years to age 90. Other key assumptions are provided in the footnote [1] below.

The chart below shows movement in investment wealth for each household to age 90:

Because the “High Ratio” household has significantly higher loan repayments than the “Low Ratio” household, it is unable to accumulate sufficient wealth to fund retirement spending to age 90 – in fact, all investment wealth is consumed by about age 80. Extended to a national basis, this does not appear sustainable.

To continue to maintain their desired retirement expenditure, the “High Ratio” household must either “trade-down” (i.e. accept a lesser lifestyle) or enter into a reverse mortgage arrangement – something that Australians are yet to embrace. But either solution raises some issues.

If many people in future are forced to sell their houses to fund their retirement because they paid “too much” for them, will the next generation also want to “impoverish” itself by continuing to buy at ratios of 4 to 4 ½? And do we want our lending institutions to take housing price risk, on a large scale, as the demand for reverse mortgages almost inevitably rises.

Varying the assumptions won’t change the essential conclusion. By borrowing and paying “too much” for our houses, the chances of accumulating enough to meet our retirement lifestyle objectives are considerably reduced. Too much wealth is tied up in housing.

Housing affordability is not measured by the loan you can service

In our view, housing affordability is not only measured by whether you are able to service a loan based on current income. It also depends on whether after servicing that loan you can accumulate sufficient investment wealth from future savings to meet your desired retirement lifestyle, without needing to extract equity from your residence i.e. by trading down or entering into a reverse mortgage.

At a 4-4 ½ times housing price to disposable income ratio, on average, this becomes more unlikely. The long term economic policy implications are potentially significant. For example, many who “overpaid” may choose to reduce their lifestyle in retirement and go on the age pension, rather than attempt to trade down or take a reverse mortgage, imposing the cost of inflated home prices on the general tax payer.

Alternatively, people may look to save more to repay mortgages quicker, putting downward pressure on consumption. Others may have no choice but to work much longer than they would have otherwise liked.

Perhaps, we are overly pessimistic and things will resolve in ways we do not foresee. However, if financial independence is important to you, borrowing heavily to buy a house at current dwelling price to income ratios will be a major drag on achievement of that objective.

[1] Key assumptions include:

After-inflation Cost of Borrowing: 4.0% p.a.

After-inflation and Tax Investment Return: 4.0% p.a.

Growth in Household Income (from Earned income) after inflation: 1.0% p.a.

Inflation: 3.0% p.a.

Expenditure to Income Ratio to age 65: 66.7%

Retirement expenditure as % of Household Income at age 65: 60%, growing with inflation

30 Year Loan Term, implying initial actual repayment of $29,362 (i.e. 29.4% of initial household income) for the High Ratio household and $11,011 (i.e. 11.0% of initial household income) for the Low Ratio household.

1 Comment. Leave new

So much of the extra income of second working spouses from about 1986 has been given to the owners of existing houses, by borrowing large amounts of money from banks which in turn was borrowed from overseas.

Every family needs tow working partners because those with two working partners constnatly bid up the prices of exiusting houses becuase they could borrow more as banks increasingly took second incomes into account in determining the amount of mortgage that could be taken.